We are aware that Vikings travelled far and wide, often a long way from their homelands. It is clear from various sources that some of these Norse travellers became members of a mercenary troupe known as the Varangian Guard. The Varangians were an elite army unit employed by the Byzantine Empire, and due to their high level of skill were deployed as bodyguards for various emperors of Byzantium. It is believed that Scandinavians made up the bulk of the unit up until the 11th century, before being joined by warriors from elsewhere.

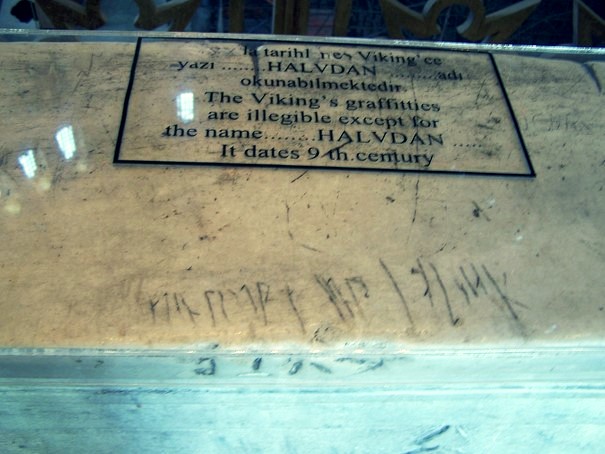

The Norse presence in the Varangian Guard is also evident through runes discovered in areas of the Byzantine Empire such as its capital, Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) and in Piraeus (a harbour port near Athens, Greece). The runes found in Istanbul are arguably more famous than their Greek counterparts but both play an important role in understanding how far some Norse warriors travelled, which in turn offers suggestions as to why. At least two individual runes have been discovered in the Hagia Sophia, one found in 1964 and the second eleven years later. Both runes have been deciphered as names, Halvdan and Árni, respectively, and there are arguments that both are just acts of graffiti, carved by possibly bored mercenaries who wanted to record their destination. It is believed the former of these was created around the 9th century (although this is debated).

Photographer: Niels Elgaard Larsen (CC-BY SA/Wikimedia Commons)

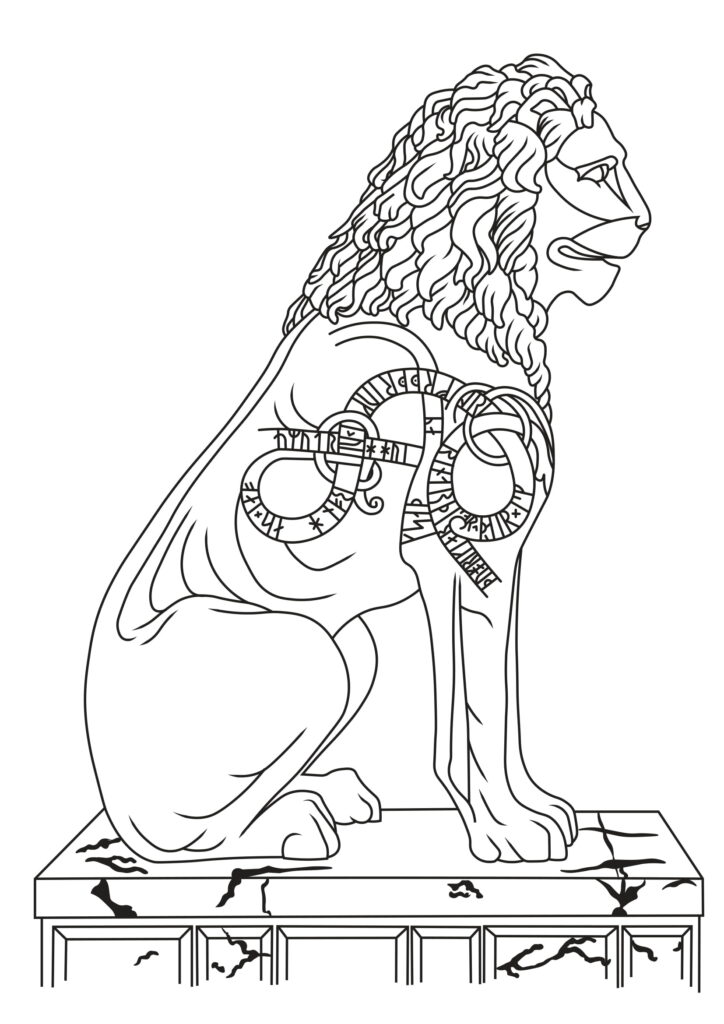

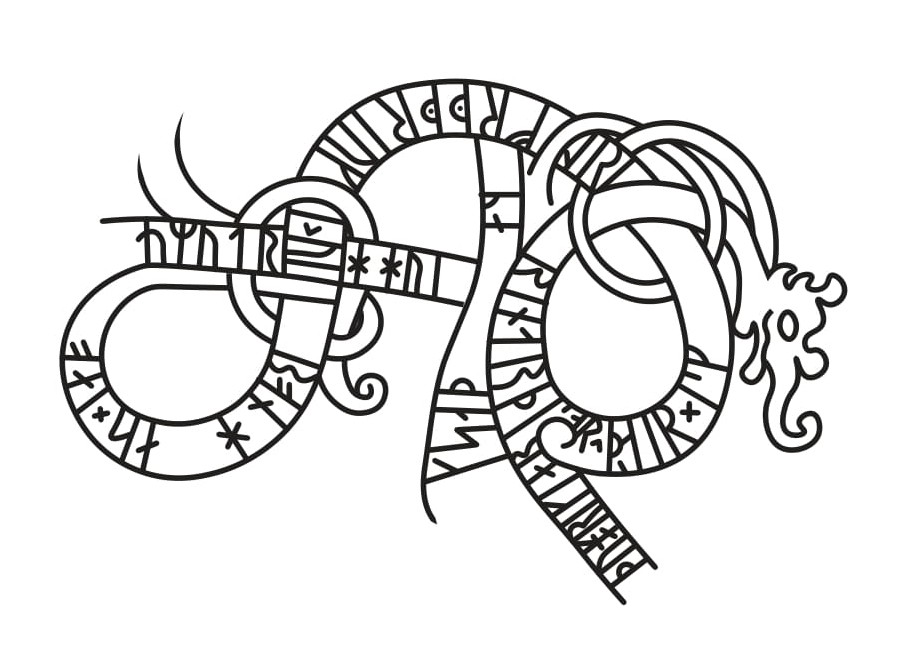

The Greek runic counterparts, meanwhile, were carved into a 3-metre-high marble lion statue, created around 360 B.C. and holding a prominent position as a gateway to the port city. The runes date from the late 11th century A.D. and are noteworthy for the length and design of the inscription: two being carved into the shoulders and flanks of the lion statue. The style is reminiscent of Scandinavian carvings and features a detailed dragon-headed scroll (a so-called “lindworm”).

What the runes depict is up for debate, due to their erosion over the centuries, however the most likely translation, posed by Erik Brate, suggests:

hiuku þir hilfninks milum

hna en i hafn þesi þir min

eoku runar at haursa bunta

kuþan a uah

riþu suiar þita linu

fur raþum kul uan farin

–

tri(n)kiar ristu runar

[a rikan strin]k hiuku

þair isk[il-] [þu]rlifr

–

litu auka ui[i þir a]

roþrslanti b[yku] –

a sun iuk runar þisar.

ufr uk – li st[intu]

a[t haursa]

kul] uan farn

They cut him down in the midst of his

forces. But in the harbour the men cut

runes by the sea in memory of Horsi, a

good warrior.

The Swedes set this on the lion.

He went his way with good counsel,

gold he won in his travels.

The warriors cut runes,

hewed them in an ornamental scroll.

Æskell (Áskell) [and others] and Þorlæif (Þorleifr)

had them well cut, they who lived

in Roslagen. [N. N.]* son of [N. N.]

cut these runes.

Ulfʀ (Úlfr) and [N. N.] coloured them

in memory of Horsi.

He won gold in his travels.

* N.N. is used to clarify that there are names missing which are illegible.

An additional study in 2014 suggested that the carvings were of a particularly high quality, and another name, Asmund, is noted as being a carver. It is possible that he was a professional rune inscriber, due to the level of detail. It is also conceivable that the runes were carved during different periods during the 11th century.

The purpose of this inscription is different from those found within the Hagia Sophia and is reminiscent of more common runestones, in that it commemorates a “good warrior” named Horsi. We are aware that it was carved by a group of Swedish mercenaries, namely Æskell, Þorlæif, and Ulfr, amongst others, who derived from the coastal area of Uppland (Sweden). The amount warriors involved in carving the runes and the design suggest that it would have taken an incredible amount of effort, and the inscription reveals that the design once featured colour. This level of dedication to honour a friend also suggests that Horsi had power or wealth, and that his fellow warriors thought extremely highly of him and wished to commemorate his story. It is also clear that the efforts of the mercenaries were not in vain, and that they were indeed successful in their roles due to the “winning of gold”.

The examples of runic scriptures from both Istanbul and Piraeus reveal that, regardless of century or location, the need to record events or even just a destination was strongly felt within those Norse who travelled far from home, some never to return.

Cover Photo: G. Dallorto (CC-BY SA/Wikimedia Commons)

Text: Alexandra Cochrane. Copywrite 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Alexandra Cochrane

Medieval historian and archaeologist from the UK, specialising in the historical archaeology of the “outland” in Scandinavia and Northern Britain. I obtained a 2:1 Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Ancient and Medieval History from the University of Birmingham and a Master of Humanities (Archaeology) (two years) from Uppsala University.

I am also in the process of completing a Master of Arts in Global Environmental History (two years). My archaeology thesis focused on identifying, locating, and contextualising a medieval region called the Ragundaskogen in eastern Jämtland (Sweden) using written sources from the Jämtland and Härjedalen’s Diplomatarium from a Niche Construction perspective.

My future goal is to complete a PhD with an interdisciplinary focus allowing me to pursue both my love for analysing texts and archaeology. In my spare time I can usually be found doing High Intensity Interval Training, cooking or snuggling up with a historical fiction novel and a dram of scotch.