Portraying and identity of Viking Age Norsemen

‘’Vikings are irredeemably male in the popular imagination,’’ (Jesch, 1991).

One can argue that the Norse Viking Age has truly defined Norway, and its heritage is still noticeable and highly relevant. It fascinates many archaeologists, but also the people. Who were these mysterious people? It is a good place to start to exclaim that the general picture of Vikings painted in television, books and other media is mostly incorrect.

The beginning of the Viking Age in Norway is marked by the attack on Lindesfarne in 793. In the following years these attacks spread all across the British Isles and Ireland. Some Norse even settled permanently in these areas. The classical Viking, as SoMe portrays them, fits this picture perfectly. There is no doubt, however, that the Vikings truly did pillage all across Europe and especially on the British Isles and Ireland. Both archaeological evidence and historical records can testify to this. Even so, it needs to be noted that the end result of many of these pillages ended in permanent settlement. Why they choose to emigrate their own country has been debated for years on end. The common conclusion is often political, economic or social reasons. The Orkneyinga saga, which is the local 14th century historical record from Orkney, paint the county as a safe haven for the Norsemen. A place to find peace and escape their problems from their home country. Many modern day people can probably relate to the idea of leaving a home to take a vacation – a well-deserved break. This, however, is a completely different view on the Viking pillagers. The barbarism they often are assigned to, is in general not accurate at all. In this article, therefore, they will be viewed as they were, regular people. Farmers, traders, smiths.

The Viking Age’s masculinity

Now that the definition of the Norse Vikings is clear; it is time to discuss the women of the Viking Age. This time period is often portrayed terribly masculine. Roles like pirates, robbers, seafarers, warriors are typical portrays of the Vikings. Men with helmets, swords and spears. Where did the women fit into this? We have already established the fact that these are often misconceptions, but either way, they are still accurate to some point. When the Vikings emigrated their own country, or decided to permanently stay on vacation, did they leave all women and children behind to fend for themselves? A tempting thought to leave your wife and children behind when you go to vacation, but you usually bring them, or?

We know for a fact that a bigger percentage of all the Viking Age graves found in Norway are identified as male graves, and the women graves are lesser. Notably, however, is that burial evidence is not always easy to interpret as either male or female. The general assumption that weapon graves belong to males and that brooch graves belong to women is not a permanent fact. Why would only women want to be buried with fancy jewelry and vice versa? I sure would love a great sword and fancy jewelry when I die. There is just not enough evidence to undergo complex analyses of the relationship between gender and graves. This is often due to the fact that it is challenging to find enough bone material to identify the gender, and the same goes for grave goods. It is often in fragments, and fragments are known to be interpretated differently by different people.

Even so, if we in this article, decide to accept the general interpretation of traditional female and male graves in the Viking Age, the percentage of male graves are strikingly high. To be able to come up with a conclusion of sorts, we need to accept this way of interpretation in lack of another. To portray the lack of female graves during the mass emigration to the British Isles and Ireland, I am choosing two very different locations to look at two very different outcomes. Dublin and Orkney are good candidates for this. According to Stephen H. Harrison’s PhD in 2008, there are in total 66 graves in Dublin and 56 in Orkney that are of Norse Viking Age origin. Out of the 66 graves in Dublin there is a number of 9 women graves. In Orkney, on the other hand, out of the 56 graves there is a number of 17 female graves. In total, there are 4 unidentifiable graves from these two places. The apparent lack of female graves compared to male are questionable and hard to interpret. What does this material tell us?

Women as passive observers?

If we ignore the richness of the grave goods in each grave and only focus on the gender of the graves, there is no mistake; there are an enormous number of male graves compared to female. It appears that the only possible role for the women of the Viking Age was as passive observers. This might point to the first argument that the males left their homeland, and with that their families, wives, children and sisters. This seems like the ‘’easiest’’ way to interpret it. Another possible argument is that brooch burial, much like weapon burial was a rite that was only practiced by a select number of the population. This is proven by archaeological studies of Viking Age burials in Norway. This leaves a questioning remark of the general interpretation of graves containing oval brooches are the only graves that contain female remains from this time period. This means that it can be hard to identify gender in many Norse Viking Age burials, due to the lack of either items. The burials in Dublin and Orkney that was deemed unidentifiable contained (amongst other things) horse skeletons, cattle jawbone, dog skeletons and ringed pins.

Are grave goods true indications of gender?

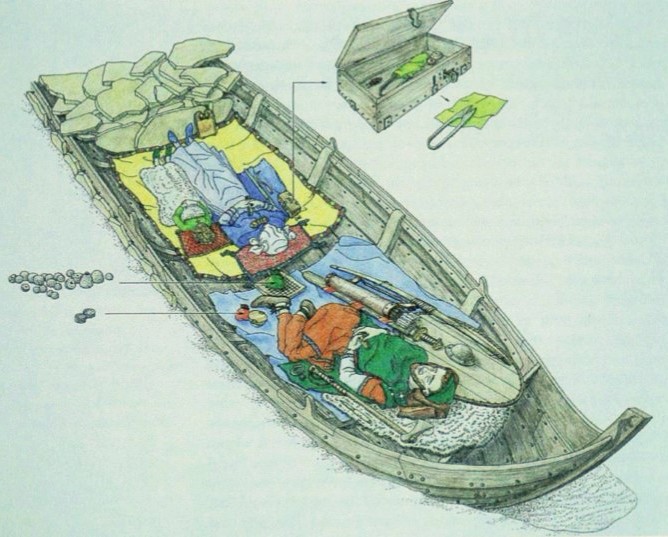

The ‘’new’’ interpretation of graves and grave goods in the Norse Viking age can bring a completely different view of the whole time period itself. If the only assumptions on gender is based, often, purely on the material in the grave, there will be an evident lack of important information. New technology and interpretations are, therefore, now able prove otherwise. It will be quite interesting to continue this research pattern and see where this might lead us. Even if there is a lack of female graves both in Norway and the British Isles and Ireland, they are still prominent figures in both sagas and archaeological material. An example of that is the boat burial at Scar in Orkney. This is probably one of the richest boat-burial finds in the British Isles and Ireland. This is a female burial, and notably, did not contain oval brooches. That the women of the Viking Age were valued in their respected societies is unmistakable. So where did they go in SoMe? Maybe the Viking Age is not as terribly male as media portrays it?

One can conclude that grave goods is not always definite truths about gender. The presence of women in the Norse Viking Age can often be overshadowed by fierce masculinity, but on the other hand still show that they had a certain prominence too. Archaeological material and historic records prove that they had a certain amount of freedom and power, previously thought unavailable. The right to property, land, inheritance and even high-status is prominent in the archaeological material. It is therefore hard to give a better conclusion on the matter of emigration, other than that graves cannot be the only factor to prove gender and that females were most likely part of this emigration.

Photos:

Cover: Dreamstime. Copyright Dreamstime.

Ship on ocean: Steinar Egeland. Copyright Unsplash.com

Ship burial reconstruction: After Olwyn Owen & Magnar Dalland, Scar: A Viking Boat Burial on Sanday, Orkney (Phantassie, 1999), fig.105. Drawing by Christian Unwin.

Text: Martine Kaspersen, 2020. Copyright Scandinavian Archaeology.

Further reading:

Glørstad, Z. T. 2014. Homeland – Strange Land – New Land. Material and Theoretical Aspects of Defining Norse Identity in the Viking Age. In: Celtic-Norse Relationships in the

Irish Sea in the Middle Ages 800-1200. Sigurdsson J.V. & Bolton, T. (eds.). Brill: Leiden & Boston.

Graham-Campbell, J. & Batey, C. E. 1998. Vikings in Scotland, an archaeological survey. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Harrison, S. H. 2008. Furnished Insular Scandinavian Burial. Artefacts & Landscape in the Early Viking Age. Ph.D Thesis. School of Histories and Humanities: Trinity College Dublin.

Harrison, S. H. & Floinn, R. 2014. Viking Graves and Grave-Goods in Ireland. In: Medieval Dublin Excavations 1962-81. National Museum of Ireland: Ireland.

Jesch, J. 1991. Women in the Viking Age. Boydell Press: Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Jesch, J. 2015. The Viking Diaspora. London & New York: Routledge.

Lange, M. A. 2007. The Norwegian Scots: an anthropological interpretation of Viking- Scottish identity in the Orkney Islands. United States of America: The Edwin Mellen Press

Larsen, A. C (eds.) 2001. The Vikings in Ireland. The Various authors & The Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde: Denmark.

McGuire, H, E.L. 2009. Manifestations of identity in burial: Evidence from Viking-Age graves in the North Atlantic Diaspora. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Norstein, F. E. 2014. Migration and the creation of identity in the Viking Diaspora. (Mastergradsavhandling) UiO, Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History.Faculty of Humanities: Oslo.

About the author

Martine Kaspersen

Iron Age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor specialized in Viking Age identity from the previous Viking Age settlement site at the Broch of Birsay and a master specialized in identity during the Early Viking Age in migrating societies in Orkney and Dublin based on grave goods from burials from said places. Exchange studies during the bachelor degree to University of the Highlands and Islands in Kirkwall, Orkney.

In my master thesis, I analyzed a total of 124 burials from Orkney and Dublin, where I attempted to distinguish different expressions of identity. This aimed to create a different perspective on the migrating societies and that they had several differences in their settlements, even though they originated from the same homeland. The main expressions of identity were gender, warrior, and religious identity.

As a writer for Scandinavian Archaeology, I am responsible for writing some of the articles presented, which is a job I am very devoted to.

Skipet på fjorden er Myklebustskipet som til daglig er hovedattraksjon i kunnskapssenteret Sagastad. Fotograf er Steinar Engeland

That’s a very good feedback. What are your thoughts on expansion on a global scale? People obviously get frustrated when it begins to affect them locally. I will be back soon and follow up with a response.

Finally a site I agree with. I have read some real rubbish today, so its a treat to read something useful.

My bro bookmarked this webpage for me and I have been reading through it for the past couple hrs. This is really going to benefit me and my friends for our class project. By the way, I enjoy the way you write.