A chill runs through your body this night, as you try to navigate your way through the night-shrouded forest. Through the canopy of the trees, you can glimpse the stars, but they offer precious little light to your journey. Somewhere in the distance, you hear the mournful but foreboding howl of one of Scandinavia’s most fearsome predators: the wolf. A new urgency to find your way home in the dark grips you, but you know in your heart it is hopeless.

Then, your fortunes turn, as the trees clear and reveal to you an earthen cottage ahead. Hardly daring to believe your luck, you hurry to the front door—there is no light in the windows, no smoke from the chimney, so you knock. No one answers. The wolf howls once again, this time much closer. Trusting to the law of hospitality, you open the mercifully unlocked door and stow yourself inside.

It is not much warmer here, so you will need something to thaw your frozen bones. You dare not return outside for firewood, but fortunately, you spy something hanging on a hook on the wall: the thick, grey pelt of a wolf. The shaggy fur looks toasty indeed, and so you carefully unhook the pelt from the wall. You wrap it around your shoulders, feeling the warmth almost immediately, and settle in to await the morning.

But something strange begins to happen, for as you grow warmer, the pelt seems to grow tighter. Your skin is beginning to itch, and your fingers and toes tingle. You also, suddenly, find yourself far more acutely aware of all the smells around you, and what’s more, you suddenly feel agonisingly hungry…and you crave meat like never before in your life. As your mouth waters at the thought, you raise your hand to your lips to wipe away the saliva, and gasp as you feel your own teeth and wonder…were they always so sharp?

Suddenly, your body seizes and you are gripped with agony. Your skin feels as though it is ripping apart. Your joints crack horribly and your bones shift as you feel your skeleton reshaping itself beneath your very skin. You fall to all fours as the pain grows unbearable, spreading to your skull and face. You try to scream in agony, but instead, the same howl you heard outside emanates from your throat…and then, suddenly, the pain is gone. You attempt to stand, but cannot. You attempt to shake off the cloak only to find yourself naked—that is, except for the thick, grey fur that now covers your entire body. You observe your paws, and you realise what has become of you.

Gripped with terror and anguish, you burst out of the door and howl at the top of your lungs into the air for help. But no one will come. If anyone else might hear your cry, they will hear only the same predator you yourself so recently feared. And indeed, despite your efforts to claw it back, you can feel your own humanity slipping away from you. You have become the werewolf.

Wolves hold a somewhat ambiguous place in the Norse spiritual realm. The archenemy of the gods is the giant wolf Fenrir, said to devour Odin at the final battle of Ragnarök. Skoll and Hati are two other giant wolves, older than Fenrir, who pursue the sun and the moon across the sky—and at Ragnarök they, too, shall catch and consume their quarry. On the other hand, we also have Freki and Geri, Odin’s pet wolves, whose role in the cosmos is little known—but their loyalty to their master is never questioned.

Then there are the werewolves—those humans cursed (or blessed?) with the burden (gift?) of lycanthropy, the ability to transform into the form of a wolf. Werewolves in Norse mythology and folklore take a slightly different form than we are used to in modern culture, where they transform only at the full moon and can turn others into werewolves with a bite. In the Norse conception, however, werewolves are not associated with the full moon, nor is lycanthrpoy said to be “contagious”. Instead, human encounters with werewolves are usually lethal, with the werewolf slaying and devouring to its heart’s (or stomach’s) content.

And how does one become a werewolf? The tale above is based on an episode from the Saga of the Volsungs, in which outlaw father and son Sigmund and Sinfjotli come across enchanted wolf pelts while lost in the woods. Donning the skins transforms them into wolves of terrifying size and ferocity, a curse which they must endure for nine nights before transforming back into human form and being able to remove the pelts—but not before Sigmund has, in his bloodlust, tragically ripped out Sinfjotli’s throat. The lesson is that Sigmund and Sinfjotli had not earned the right to wear these powerful artefacts—they took something that did not belong to them, that they did not understand and could not hope to control, and they were overwhelmed.

The good news, then, is that the werewolf transformation might not always be a permanent one. But there are other episodes of people transforming into wolves in which the manner of the transformation is not specified—or whether or not it was involuntary. The ability to transform into a mighty wolf at will might be a very useful skill indeed. And there is some archaeological evidence that such a symbolic transformation might have occurred on the Norse battlefield.

We have all heard of the berserkr (plural: berserkir), often referred to as the “bear warrior”. But in addition to this, we hear also of the ulfhedinn (plural: ulfhednar), the wolf warrior. One hypothesis has it that ulfhednar were a specialised warrior class, who fought with spear and shield and may have worn wolfskin cloaks into battle. It is possible that ulfhednar and berserkir represented champion warriors hand-picked by a king or jarl to serve as elite forces on the battlefield, or as his personal retinue (or hird). Harald Finehair, one of the most famous Viking Age kings of Norway, is said by sagas and poetry to have travelled with a bodyguard unit dressed in wolfskins, who howled, shook their spears, and bit their shields before battle, where they fought valiantly and in disciplined formation. A far cry from the mindless monsters of Sigmund and Sinfjotli’s misadventure, which might suggest that lycanthropy was a skill that had to be mastered, or earned.

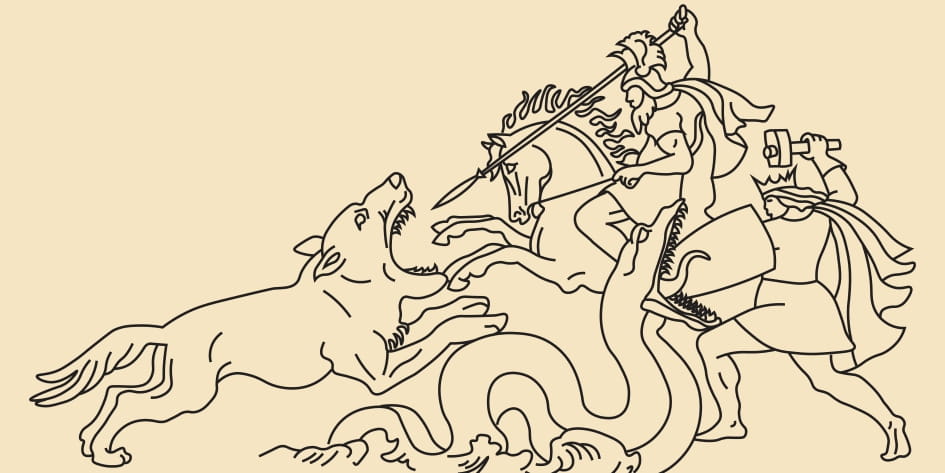

As for archaeological evidence, sadly none of these supposed wolf- or bearskin cloaks has been found (although some graves feature bear claws which suggest the person was buried wrapped in a bearskin). However, what we do have are metal stamps and engravings picturing humanoid figures with the heads of wolves, armed with spears and swords. A famous example (pictured above) from the Vendel Period comes from Torslunda on the island of Öland, modern Sweden. The figure accompanying the wolf warrior is identified as Odin due to his missing eye, furthering the connection of wolf warriors with kingly or lordly figures, and of the connection between Odin and wolves. Artefacts bearing a similar wolf warrior motif have been found throughout the Old Germanic world as far back as the Migration Period, and earlier still, Roman sources attest to the presence of so-called “wolf warriors” among the ranks of the German peoples they encountered. It is possible, then, that the ulfhednar of Scandinavia were the Norse version of this ancient custom, and that the legends of human–wolf shapeshifters—werewolves—arose in conjunction with this phenomenon.

Belief in werewolves, or something like them, is unaccountably ancient and widespread, and persisted even into the early modern period. Knut the Great, the Viking king of Denmark, Norway, and England in the early 1000s, felt the need to make specific mention of werewolves in his ecclesiastical law codes. Later, alongside the infamous witch trials in Europe and North America in the 1600s, some people found themselves accused of lycanthropy and ended up subject to the same cruel punishment as alleged witches.

Clearly, then, the human fascination with wolves is an enduring and mixed one. Wolves are viewed both negatively and positively, and an affinity with them is something to be both feared and respected. And so, should you ever find yourself staring up at the moon and hear the howl of a wolf in the distance, remember that that shiver you feel running down your spine is a shiver that has been felt for millennia.

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover illustration and mid illustration: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Archaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada) and a Master of Arts from Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden). My specialisation lies in bioarchaeology broadly, with a primary focus on mammalian zooarchaeology, and a special interest in the Late Iron Age of Scandinavia (though you can occasionally catch me sniffing around Egypt as well).

In my Master research I conducted an osteological analysis of domestic dog remains from Valsgärde cemetery, Sweden. The aims were to identify the number of dogs buried at the site, reconstruct the appearance of the dogs, and identify any patterns and changes between the Vendel Period and Viking Age.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between humans and animals, domestic and wild, in societies throughout the world. Through archaeology, I hope to shed light on this crucial part of our shared heritage.