As of today, a whole year has passed since Scandinavian Archaeology launched! And a lot has happened since! Our team has grown and changed, and we are so grateful for all the talented archaeologists who have joined us and contributed over the year that has passed.

We have made many posts about many topics, high and low, and we have had the honour to publish a lot of interesting and well-written articles. We are looking forward to yet another year filled with absolutely amazing work from both our writers and editors, but also other archaeologists and historians.

Our goal is still the same, to spread Scandinavian archaeology to all our readers in a well-packed popular science format. We who work at Scandinavian Archaeology are all archaeologists and we love what we do, and we love to share our knowledge with you and hope to do so for many more years to come.

To mark the one-year anniversary, we have done several things.

First off, we have below listed our top five most read and spread shorties from our social media over the last year. We hope you enjoy browsing them below, either for the first time or perhaps again.

Secondly, we have started a Patreon for our fans to support us with. We hope you will become either a Niding, a Thegn, A Huskarl, a Jarl, or perhaps a Völva?

https://www.patreon.com/ScandinavianArchaeology

And for last, we will have a small giveaway! To enter, please follow the instructions on our Facebook post that we will post tomorrow the 2nd of November. We wish you good luck!

We thank you so much for the past year, new as old readers, and we are looking forward to your visits again and again!

All the best,

Lovisa, Chris, Molly, Nicoline, Martine, and Anna

1. The trolls from Norwegian folklore

The troll is a famous ancient being who often appears, typically, in Scandinavian folklore and Norse mythology. Their characteristics vary, depending on the source; they can be big, ugly, and slow, or look and behave like human beings. This is exactly what makes them terrifying. However, the trolls from Norwegian folklore are even more terrifying than the ones that look like humans. They are usually identified as gigantic, terrifying, hideous, and most importantly, man-eating. But fear not, they can only be found deep, deep in the woods, where we usually never wander, or dwelling in the mountains far up north in Norway. Their close connections to the underrealms, where the Huldra and Vettene dwell, only heightens their frightening aura. These creatures were so deeply feared and loathed by the local communities, that the earliest Christian laws from the 11th and 12th century CE state that people are under no circumstances to contact or seek knowledge about trolls. Even to this day, children are told stories about these monstrous beings, who love to taunt and devour children for breakfast. In every storybook, these beings were always present. If you ever have the—rather questionable—wish to encounter one, you must do so during the hours of the night. Trolls can only roam freely during the hours where the sun does not shine; if they ever venture out of their caves during daylight, they will immediately turn to stone. You may see some of the unlucky ones standing tall as mountains in the Norwegian wilderness, turned to stone for eternity. Fortunately, they are seldom clever, these trolls—and one can often outsmart them. So, if you are ever so unlucky that you encounter a troll in the Norwegian wild, all you need to remember is to try and keep your wits. If you are lucky, you may survive. If you are not…well, then you just satisfied the hunger of one of the many trolls that dwell in the depths of the seemingly endless forests of Norway. Good luck.

Text: Martine Kaspersen. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

2. The Øverby Runestone: an incredible find

You asked for it, and here it is: the Øverby Runestone! This particular runestone predates the Viking Age, typically associated with these monuments, by 400 years. Most runestones discovered in Scandinavia are dated to between 900 to 1000 AD. There are only few known exceptions to this rule, one of them being the newly discovered Øverby runestone, which dates to approximately 400 AD. The stone stands almost 3 meters tall, and a little over 1 meter in width. The Øverby runestone was discovered in Norway in 2017. It may sound strange for a runestone to be discovered so late, but there is good reason for this. It served as a step in a staircase for almost 100 years, until the house it belonged to was torn down in 1990. After that, the stone was placed in a garden of an elderly couple, where it served as a coffee-table for nearly 30 years! Although the couple had noticed that there were some strange lines on the side of the stone, it wasn’t until they sent a photo into a local newspaper that the runestone was actually discovered. The runic inscription, written in Elder Futhark, reads as follows: “Lu irilaR raskaR runoR” This roughly translates into: “Carve the runes, oh skilled rune master.” This runestone is the earliest documented example of the Old Norse word “raskaR” (skilled), a word lost in the modern Norwegian language. The runestone is therefore not only of importance for archaeologists and historians, but also something for linguists to ponder.

Text: Molly Wadstål. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

3. The helmet from Valsgärde 7

The helmet from Valsgärde 7 is a beauty. It is from the Vendel Period (500-750 AD), also known as the “golden age” of Scandinavia as a lot of the artefacts in elite graves during this period are made from gold or have gold plating. The Valsgärde grave field in Uppsala, Sweden is just a short walk from Gamla Uppsala, known for its royal burial mounds. Valsgärde has no mounds, but it is home to 92 known graves, of which 15 are ship burials. Grave fields containing ship burials can be found all over Scandinavia, although they are not very common compared to other grave types such as simple pit graves, cremation graves, or chamber graves. Valsgärde is unique in this collection of burials as it is the only grave field containing ship burials that hadn’t been plundered before excavations took place—in Valsgärde’s case between 1928 to 1952. Helmets are not a common artefact find in Scandinavia, but because Valsgärde has stayed intact, a whopping four beautiful helmets have been found here. The helmet from Valsgärde grave 7 is decorated in garnets, gold, and decorative sheets of metal with different mythological motifs. It (and the others from Valsgärde) bears a great resemblance to the Sutton Hoo helmet in England and the helmets from Vendel in Uppland, Sweden.As an attentively eye might have noticed, it is similar to our logo, and that is because our logo is based on the Helmet from Valsgärde grave 8, so a sibling to this helmet!

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

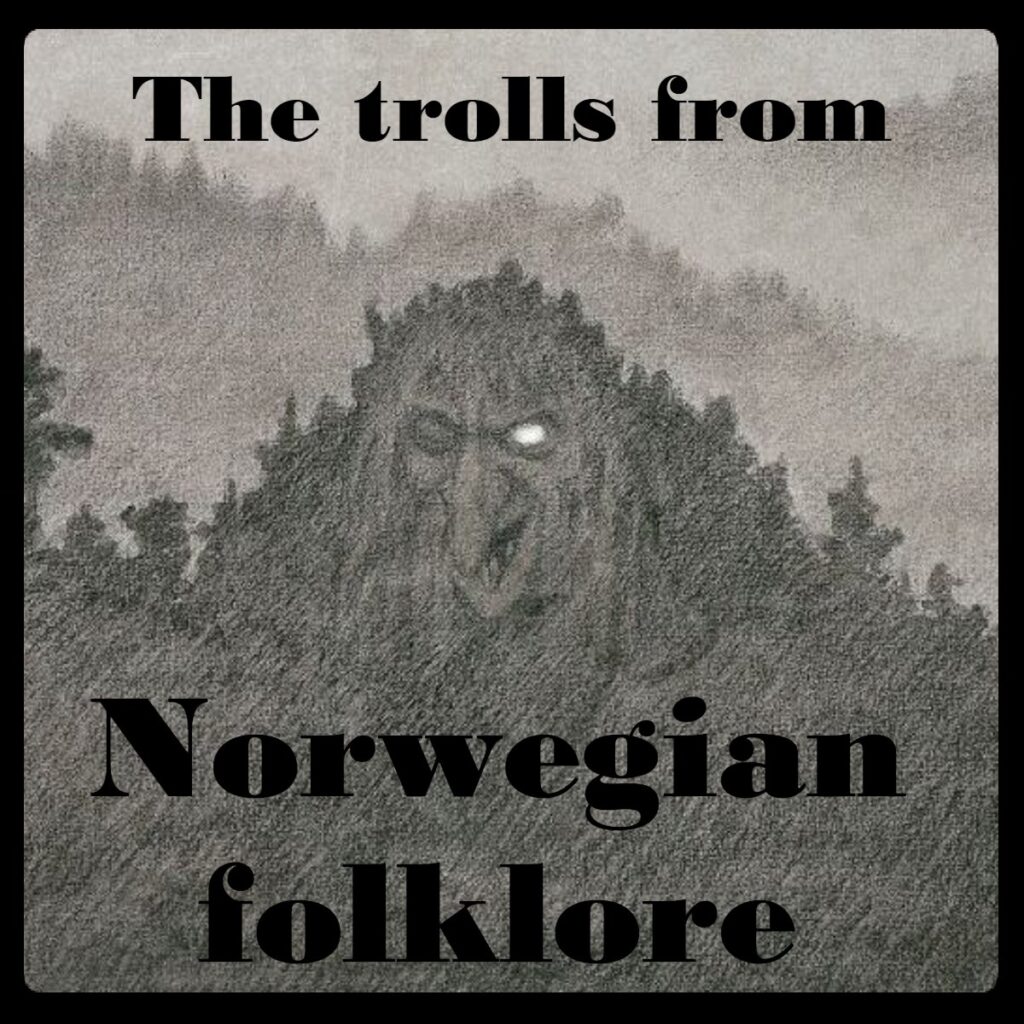

4. The Tullstorp runestone

The Tullstorp runestone is a beautiful stone with unique decorative motives, such as a Viking style ship and a beast, believed to be a wolf. The stone dates back to around 1000 A.D. and stands two meters tall. The original placement of the runestone is unknown but was first discovered and historically noted around 1600. It was repurposed as building material for a church wall in 1624 in Tullstorp. It may sound bizarre to place a runestone inside a wall but using runestones as building materials was not an uncommon occurrence, even as recently as a few hundred years ago. This practice ceased once the historical value of runestones was appreciated. The monument was rediscovered when the church was torn down over 200 years later, and was reused in a different church wall, until it was finally moved to its current location. The runic inscription reads (in Latin letters, Old Norse, and English translation): × klibiʀ × auk × osa × ¶ × risþu × kuml + ¶ þusi × uftiʀ × ulf + Kleppir/Glippir ok Ása reistu kuml þessi eptir Ulf / Kleppir/Glippir/Kleppe and Ása/Åsa raised these monuments after Ulf/Ulfr/Ulv. The decorative motif has various interpretations but are believed to be artistic renditions of the ship Naglfar (“Nail-traveller”) and the wolf Fenrir from Norse mythology. The wolf head on the serpent band, the ship, and the beast is believed to reference Ragnarök (or Ragnarǫk), which is the Nordic rendition of the apocalyptic end of the world. The forementioned Ulf/Ulfr/Ulv can also refer to Fenrir, as it is an ancient Nordic word for wolf: alternatively, it was the man’s name which inspired part of the motif.

Text: Molly Wadstål. Copyright 2021 Scandinavin Archaology.

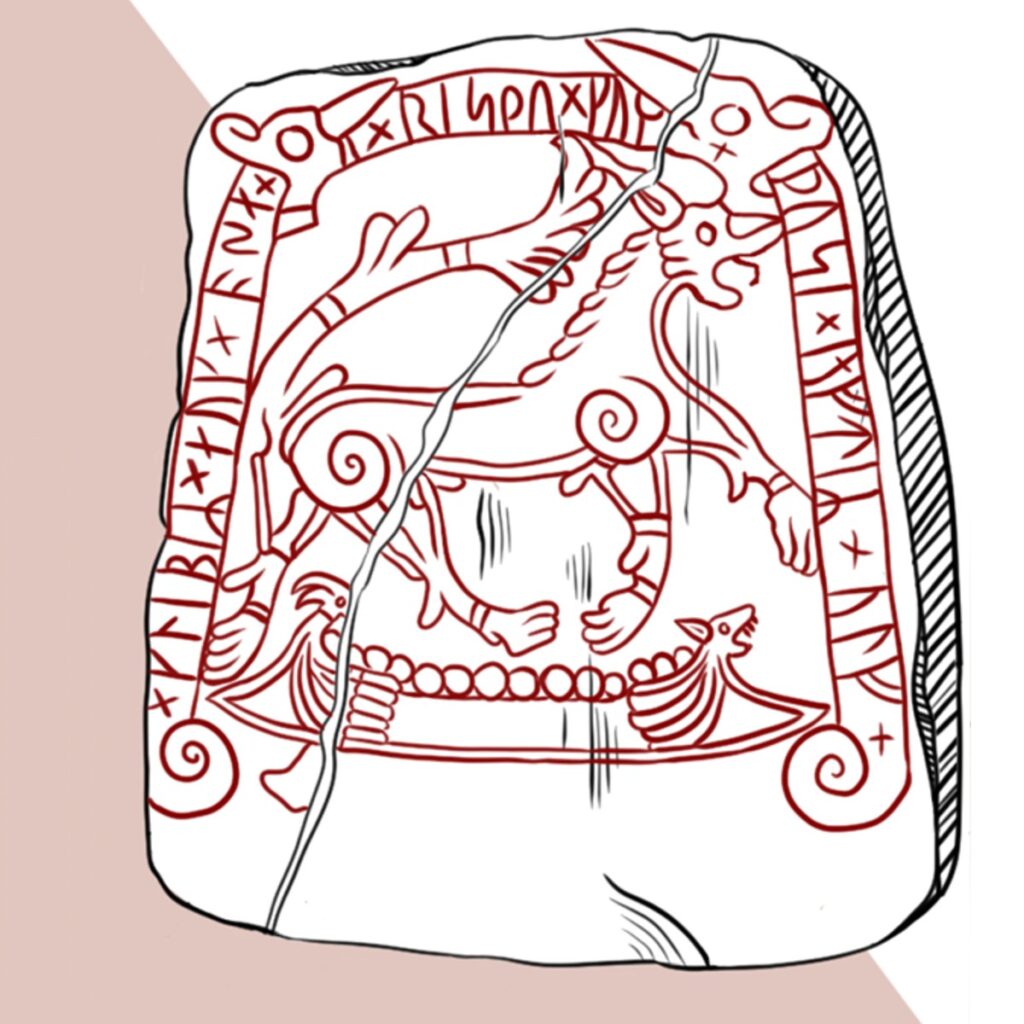

5. Doggerland: vanished, but not forgotten

10,000 years ago, Britain was connected to continental Europe and Southern Scandinavia through an area known today as Doggerland. This area would have been fertile consisting of meadows alongside the coast and would have been home to numerous Mesolithic communities and settlements. What happened to it and where did it go? Just over 8,000 years ago, a previously believed catastrophic tsunami occurred as a result of the largest known submarine landslide “the Storegga” just on the coast of Southern Norway. It was presumed the natural disaster acted as a kiss of death to the communities residing here. New research suggests this was not necessarily the case and some parts may have survived even 1,000 years after the event. Here we assess how rising sea levels and natural disasters, problems in today’s world, would have affected the region. ‘Doggerland’ is generally used as a ‘one-size fits all’ term, meaning the submerged landscape that at its maximum stretched from Yorkshire across to Denmark. However, this area was at risk from rising sea levels which would decrease the physical landscape.

A 1,000 years later, a vast majority of the area would have already been submerged with only the highest areas still visible, forming a small archipelago around the largest island “Dogger Island”. How large the habitable area would have been being questionable as the landscape due to the formation of estuaries, islands, and inlets. It is believed that between 8,400- 8,200 years ago, sea levels rose again between 1 and 4 meters globally, of course influencing Doggerland. If waters rose by the maximum, it is thought Dogger Island would have been reduced to a shallow sandbank with some high lying islands visible, a total landmass of c.1,000km2. These were however swallowed by the sea only 800 years later, over 1,000 years after the tsunami. Look out for the next installment of Doggerland for more on the area and the new research!

Text: Alexandra Cochrane. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.