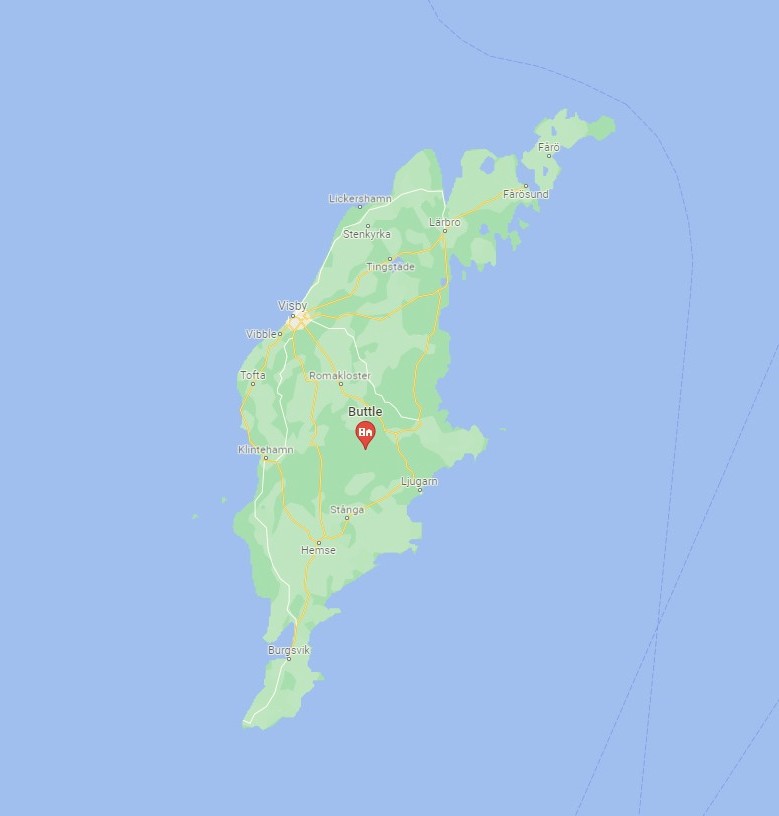

Quite recently, Uppsala University released news of a remarkable grave find at the site of Buttle on the island of Gotland, Sweden. The grave—containing a warrior from the Roman Iron age (0-400 A.D.), equipped with a spatha sword and spurs—is a once-in-a-lifetime find. The site of Buttle was once the center of one of Gotland’s main roads, and therefore holds a significant place in the landscape that has been the site of both buildings and other use for at least 2000 years. Making this find extra special, it was found by students during a seminar dig. Our editor-in-chief Lovisa Sénby Posse, who holds Buttle close to her heart—as it was her first excavation—called Alexander Andreeff Högfeldt, the dig leader and her previous teacher, to ask a few questions about the grave, the warrior, and the context.

Today, Buttle consists of meadows and pastures for Gotlandic sheep to graze during the summer. The place also holds an historical farm and the stone foundations of three houses dated to c. 200-600 AD. The cultural landscape around Buttle testifies not only to its use over a long period, but that it has also been used with continuity. The remains of settlements, agriculture, metal shops, graves, and ritual activities can all be spotted in the archaeological record from the Roman Iron Age up until modern times. The site also holds stone formations, grave fields, and two picture stones from the Viking Age (750-1100 A.D.)—the Gotlandic alternative to runestones, featuring instead of runes. It is because of these picture stones that excavations have been taking place at the site since 2013: the aim of the long-term project Uppsala University is conducting at the site is to investigate the relationship between the placement of picture stones in the landscape and older Iron Age settlements.

Alexander Andreeff Högfeldt explains to me that the grave did not come as a surprise. In 2019, the site was excavated, and two concentric stone circles— the larger circle about 9 m in diameter with a smaller one inside—were found under a large pile of rocks. In the middle of the formation, a slab of slate was located, which indicated that a burial might be placed underneath. However, there was no time in 2019 to excavate the grave, and during 2020 there was no opportunity to dig, hence why the grave was excavated only this year. When the slate was removed, it was first believed to be a cenotaph—a grave monument without a body. The reason? The skeleton was only eventually found unusually deep down in the ground, down to 1.5 m, and therefore the students and archaeologists did not at first think there was anyone there to find.

The warrior was laid in a fetal position, with his head to the north and his face to the east, embracing his sword between his arms and legs. On his feet, he had spurs with silver filigree and bronze fittings, indicating he was a rider. The sword also testifies to this, as it is a type of sword called a spatha, used by Roman cavalry. The sword is approximately 80 cm long and made from iron, and was buried placed inside its wooden scabbard. The sword has fittings and a wooden handle with a ferrule made of bronze. That is the metal piece protecting the tip of the scabbard. These types of swords dates to the Roman Iron Age and were often used by Germanic troops who served as mercenaries for the Roman Empire. Andreeff Högfeldt says that it can not yet be said for sure if the warrior was one of them, but it is indeed a thrilling thought.

The grave also contained two knives, a belt buckle, and above the individual’s head, a ceramic container was located together with a container made from organic material. The warrior has been determined as a male, not by the nature of the grave goods, but by the osteological remains: the skeleton. Campus Gotland, Uppsala University, has an osteological department, and the skeleton has therefore been given a preliminary sex determination based upon typically male traits in the skeleton: a defined brow ridge, a distinct angle at the jaw, a protuberance at the back of the head, and of course, the most reliable card, the shape of the pelvis.

But the warrior was not the only individual found in the grave. Around the outer circle, the remains of at least two infants were found who had lived, in an unexpected twist, during the much later Vendel Period (500-700 A.D.). In between the outer and inner circles, a charcoal layer was detected containing burnt human bones. This means the grave has been used for additional burials through the ages. This is not the only grave at Buttle, either: at least 2-3 grave fields are in the area, and last year, another grave from the same period was found in the same fetal position as the warrior, but without any grave goods, and—even more peculiar—without any arms.

Andreeff explains that they have no idea what might have happened to the other individual’s arms. There were no signs of trauma, such as cut marks on the skeleton or remains of the upper parts of the arm. Sometimes, graves are robbed and not only for grave goods, but also for bodies, or body parts. However, something which contains so many small bones as a hand would most likely have left some indications behind, such as finger bones (as these are easily missed by grave robbers), but in this case no remains from hands nor arms were found. It is still a mystery we hope someone might shed some light upon in future research, but for now, it is indeed a very interesting addition to the individuals that are buried at Buttle.

The warrior find is fascinating and gives a broader context to Buttle and Gotlandic history. Other archaeological finds found at Buttle indicate a connection to the continent as well as evidence of a warrior presence. A spearhead, as well as buttons for warrior shirts, have been found. However, they have not been dated as they lack any distinct decorations that are otherwise used to date inorganic materials (which cannot be carbon dated). Items that testify to trade or war are the three silver Roman coins and Mediterranean beads found in the Buttle context. Andreeff says these are intriguing: are they war booty or the result of trade, and if so, did the people at Buttle travel all the way to the Mediterranean themselves, or was the trade conducted through middlemen? Or was it simply payment? It is still an ongoing question.

The warrior find will provide good support for future research regarding Buttle, not only in and of itself, but also as a comparison to material from Vallhagar: another Gotlandic settlement, contemporary with Buttle and featuring three grave fields. The grave can also be compared to other graves of similar type on mainland Sweden.

So, what will happen to the Buttle warrior now? In keeping with the archaeological course of action, the skeleton and the items are brought back to the university for analysis. The artefacts are cleaned and sent for conservation, while the skeleton is given a full osteological analysis. These types of analyses are extremely helpful in giving clues to an individual’s life, including things like health and sickness, muscle mass, stature, age at death, and trauma, just to mention a few, which can often be detected from the skeleton. Other than this, samples will also be sent for carbon dating, isotope analysis, and DNA analysis which can determine additional information such as what the person ate, where he came from and where he had traveled, when he died, and many genetic traits that cannot be seen in the bones. When all the samples are gathered and the material has been analyzed, it will then be given to the Gotland Museum, according to Sweden’s policy of handling of archaeological remains.

The Buttle warrior is a piece of the puzzle to understand Buttle more specifically, but also Gotland in general. Only time will tell what new information this incredible find will bring to light.

Cover photo: Alexander Roesen Sjöstrand. From a 3D picture of the bottle warrior grave. 2021. Uppsala University.

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.