The Middle Ages, also called the medieval period, are not part of Christian Jürgensen Thomsen’s “Three Age System”, which consists of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. This period is not prehistoric, but nor is it quite modern—it is, hence its name, a common way of describing the diversion between the prehistoric time periods and the modern era.

The Middle Ages are still considered to comprise an archaeological period in Scandinavia, but this is also the first period that could be studied through historical archaeology—that is, by comparing archaeological findings with contemporary literary sources on a large scale. As such, it is something of an anomaly—not defined by any particular material or technological trend, nor by any specific system of belief. It is the bridge from the ancient world to the modern.

The beginning of the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are usually marked by the end of the Viking Age around 1050-1100 AD (depending on country). The end of the Viking Age and the beginning of the Middle Ages is defined by several factors: most notably the shift in religion, from the pagan faith to Christianity; but also the cessation of typically “Viking” activity like yearly raiding and the reformation of the old Scandinavian social order into a form that mimicked the kingdoms of the European continent. These things all occurred gradually, and at different times in different countries—but the move from one period into the next is always transitory, not sudden.

In continental Europe, the Middle Ages are taken to have begun much earlier (in the century or two following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, starting roughly in the 5th c. AD), and lasted well over 1000 years until the Enlightenment and Reformation period. However, only 500 years separated the start of the Scandinavian Middle Ages and the Reformation, which began in 1536 in Denmark, 1537 in Norway, and in Sweden 1527-1600. So, in Scandinavia, the medieval period has to be defined in somewhat different terms than elsewhere in Europe. The Scandinavian Middle Ages are often separated into three periods: the Early Middle Ages (c. 1050-1200); the High Middle Ages (c. 1200-1350), which ended nastily with the Black Death in 1349; and the Late Middle Ages (1350-1526/27).

So, what did the social world of the Middle Ages look like in comparison to the Viking Age that preceded them?

Christianity in Scandinavia

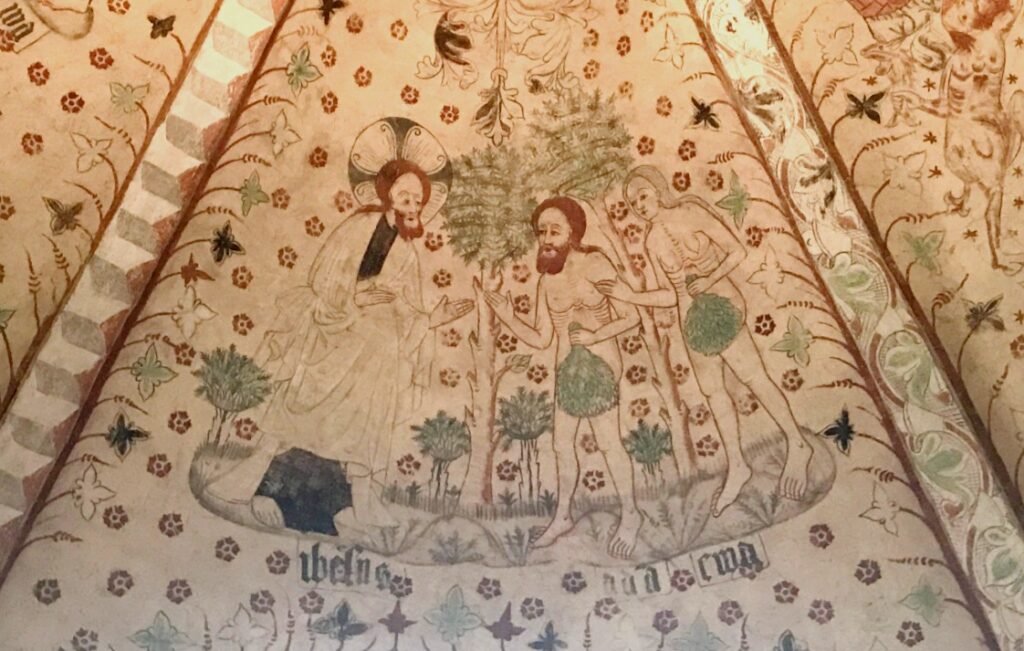

By the start of the Middle Ages, Christianity was the ruling religion in all of Scandinavia, and many of the European standards of churches, bishops, priests, and holy kings were applied as a general rule in Scandinavia. This shift became a key marker of the end of an era, even though it took a long time to completely establish Christianity in the Scandinavian society. Denmark was the first Norse kingdom to Christianise in the mid-10th c., but this kingdom is still taken to have been a “Viking” kingdom for the next hundred years. However, as this change took hold, the Æsir and Vanir no longer ruled the Norse mythology; the power of the jarls and their personal networks diminished; and, importantly, a visible change in burial practice appears in the archaeological record. Grave mounds became illegal, and everyone had to bury their dead at a common, Christian, burial ground with no visible traces above ground (except perhaps a tombstone). Christian graves also lack nearly all grave goods and personal belongings and the only way to tell, for example, social status is through the placement of the graves on the churchyard—the closer to the church, the higher the status. Archaeologists have always used graves in order to try to understand past belief systems, and the lack of grave goods makes this task more complicated (aside from telling us the basic fact that this new faith did not demand grave goods!). However, since the new religion is one enshrined by literary sources, this helps us overcome this obstacle.

The switch to Christian beliefs, and the endorsement of church power was a strategic and appropriate move for kings. Even though Scandinavia is located far north, the Scandinavian elites were, contra popular belief, very knowledgeable about the trends on the continent. And for ambitious kings wishing to remake themselves in a “European” image, a change to the overwhelming religion of the continent was not only a strategic move but also a new way to contain power: not only was the church a powerful institution with access to power and riches, it also featured a bureaucratic structure of authority that gave advantages to the elites. The elites of the Scandinavian society could also, by changing religion, improve their standing among the other elite rulers of Europe, making it easier to form alliances and have their authority recognised by their neighbours.

This religious shift suffered a few setbacks along the way, some of them violent. But in general it seems, again, contra to popular belief, to have been a relatively peaceful transformation, with pagans and Christians living side by side in the late Viking Age and even, in some cases, syncretising their beliefs. Pagan worship was still allowed in these early centuries, though not necessarily out in the open—these practices were likely restricted to the home. By the Middle Ages, however, pagan practice had been fully outlawed.

The period 1250–1350 has been characterised as the peak of ecclesiastical power in the Middle Ages. The archaeological material and historians alike have argued that the growth of the monarchy and church during the High Middle Ages, meant that these two social powers took, increasingly, over important functions in society—especially law enforcement. This resulted with the lower-class society being politically incapacitated, no longer with the ability to enforce law on their own, as they previously had.

Feudalism and economy

The establishment of the feudal system also became a successful way of managing the Scandinavian countries. In the typical feudal society, social, economic and political relations were characterized by personal and mutual ties in a strong hierarchical order. Briefly, the king sat at the top of the ladder with the whole kingdom being “his” domain; beneath him were nobles who stewarded their own subsections of this domain, land which was worked by the peasantry (serfs) in return for the noble’s protection. At least, that was how it worked at its best—in reality, this was often a rather violent period, and many lower-class people suffered at the hands of the wealthy in society. However, the feudal system was not quite as strictly-applied in the Scandinavian countries as in the rest of Europe. This made it easier not only to establish, but to maintain peace, and allowed peasants to retain more power relative to their counterparts in many European kingdoms. Kings were also formally “elected” during the Middle Ages by their nobles, in contrast to the automatic royal inheritance elsewhere.

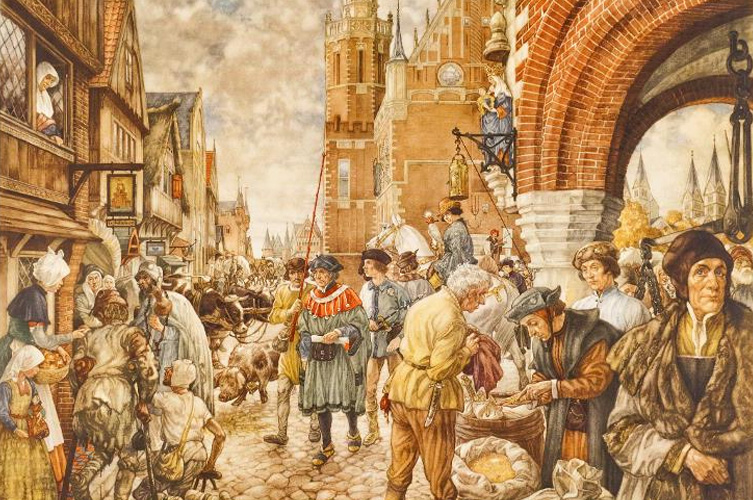

Most still lived in rural settlements, as farmers or as craftsmen. Outside the feudal countryside, some of the towns that had emerged in the last centuries of the Iron Age—such as Aarhus in Denmark, Oslo in Norway, and Sigtuna in Sweden—grew larger and became central places. Usually these towns would be left in the hands of royally-appointed officials. Another class of people who grew in station during this time were merchants, operating out of coastal cities like Visby in Sweden and Bergen in Norway. For its own part, Sweden also joined the Hanseatic League—a trade alliance of mercantile towns and guilds that stretched across much of Northern Europe.

Ruling in Scandinavia

The monarchy and kingdoms in Scandinavia grew rapidly in power during the Middle Ages. This was mainly supported through dynastic marriages, by which both the Norwegian and Swedish monarchies gained direct interests in Denmark—though the origins of these struggles date much further back in time. From around the period 1300, an originally domestic struggle for the Swedish throne developed into a power struggle between the Norwegian–Swedish and the Danish–Swedish alliances. In this triangle, the three kingdoms were so strongly connected to each other through both marriages and political interests, that it ultimately became impossible for Norway to isolate itself from the power-developments in Sweden and Denmark. This would ultimately result in the development of the Kalmar Union—a unified Nordic kingdom for the first time in history. The Kalmar Union lasted from 1397 until 1523, when the Swedish king Gustav Vasa seceded in 1524. Sweden was now a completely independent kingdom, while Denmark and Norway remained united (though, in practice, with most of its power concentrated in Denmark).

The Black Death

Though the Middle Ages were not uniformly miserable, as is often imagined, the Black Death strongly tints our view of the time period—and no wonder, as it wiped out an entire third of Europe’s population. Scandinavia was no exception. The plague that tormented large parts of Europe spread through all Scandinavia in a period of two years beginning in 1349. In a very short amount of time, the plague took the lives of about a third of the entirety of Scandinavia’s population. This is clearly visible in the archaeological material from this particular period, when mass-graves, new items for personal protection, and entirely deserted farms and villages can be seen in the archaeological record.

Conclusion

The medieval period was a new era in Scandinavian, with not only a new religion but also new power structures that reinvented the society from the ground up. The church successively became more powerful and thus had more power over the people, and as bureaucratic establishments grew larger, it also became possible for rulers to gain more power. The seeking of the thrones of Scandinavia led to marriages and political alliances that bound the countries tighter together than they had ever been before.

Most of today’s major Scandinavian cities rose to prominence in the Middle Ages, and this period is still visible through churches, castles, walls, and roads. In Stockholm, you can still visit the famous Gamla Stan (Old Town), a neighbourhood established in the city’s very earliest day.

The Middle Ages have an unpleasant reputation in the modern imagination, in no small part as a result of popular culture often portraying it as a period of unending death, torture, and sickness. But this is, as always, only part of the picture. The society of the Middle Ages became became more organised, and many people flourished as legal protections became more enshrined under the guidance of the church. It was also a time of sometimes violent hierarchical oppression, and it was marked by one of the deadliest events in human history—the Black Death, which severely disrupted the flourishing society. However, as always, the Middle Ages established the foundation for the next society to follow it: the Early Modern period, beginning roughly in the 17th c., which would eventually evolve into the society we live in today.

This ends our whirlwind tour of the pre-modern “ages” of Scandinavia. Of course, articles like ours are far too short to explore every important detail of the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, or Middle Ages, and certain subtleties, variations, and events have not found their way onto our pages. But we hope you have come away from this with a broad overview of the trends that characterised these periods, as well as some understanding of the complexities of one age transitioning into another, and perhaps with a yearning to learn more about them. We will, of course, be happy to oblige.

Thank you for joining us!

Cover Image: Valdemar Atterdag brandbeskattar Visby by Carl Gustav Hellqvist (1882).

Text: Martine Kaspersen, Lovisa Sénby Posse and Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2022 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Literature

Bagge, S. (1999). The structure of the political factions in the internal struggles of the Scandinavian countries during the High Middle Ages. Scandinavian Journal of History, 24(3-4), 299-320.

Bagge, S. H. (2019). Tronfølge og borgerkrig i Skandinavia i middelalderen.

Christophersen, A. (2020). Under Trondheim: fortellinger fra bygrunnen. Museumsforlaget.

Orning, H. J. (2014). Borgerkrig og statsutvikling i Norge i middelalderen-en revurdering. Historisk tidsskrift, 93(2), 193-216.

Pedersen, B. A. (2019). Konflikter i middelalderens Norden-En introduksjon. Collegium Medievale, 32(2).

Svensson, R. (2021). Periodiska myntindragningar: En utvecklingsfas under svensk högmedeltid. Historisk tidskrift, 141(1).