What do sticks and stones have in common, except that they both can break your bones? Well, they are both good for carving runes on!

Runestones, most of you are familiar with. The reason for this is that they have withstood the test of time and are to this day still standing tall in the landscape, testifying to the faith of people who lived a long time ago. However, runestones were not the most common place to carve runes: in fact, they were quite costly to make and required a professional stone carver. But runes were also carved, not by professionals, but by regular (and probably free) people. The only difference is that these runes were carved on wood or bone, and as the limited archaeological record shows, the messages they held were quite different compared to the magnificent stones. While the runestones were a testament to someone’s life and prideful death, rune sticks bear witness to people’s lives in more everyday situations. They were almost used as today’s Post-Its, containing small messages or notes.

As they were primarily made from wood—the most accessible material—most of them have decayed, but there is still quite a nice collection of them left. The most important collection of rune sticks comes from Bryggen in Bergen, Norway, and was discovered in 1955. It contains about 670 medieval rune sticks from the 14th century, all of which are made out of either wood or bone. The find is remarkable and holds great importance regarding rune research in two aspects.

First, these have added a whole new point of view on the usage of runes. Before, it was believed that runes were only used for names or for formal use, such as on runestones. But the Bryggen find shows that runes were used for everyday writing such as notes, messages, labels, correspondence, business deals, religious texts, and some even have an erotic theme to them. The most comment rune inscription was, however, Eysteinn á mik (“Eysteinn owns me”), used as a label of ownership on items. The religious text were many times written in Latin, such as Rex Judæorum In nomine Patris Nazarenus, and are believed to have been used as protective amulets. Regarding the erotic themes, we will not deprive you of it: Féligr er fuð sinn byrli Fuðorglbasm, meaning “Lovely is p***y, let c**k fill it.” Racy stuff!

Another stick that corresponds well into this day is translated as, “Gyda is telling you to go home”. It is believed to have been carved by what we can imagine was a quite angry wife of a husband spending too many late hours at the local tavern. There are runes on the same sticks believed to be the reply to the request, but they have not been translated, so we do not know what Gyda’s husband decided to do. Bur regarding there was a reply on the stick, we can assume he decided to stay instead of coming home himself. There is also another stick talking about an escalating fight in the area, although we do not know if they are related.

These examples show the variety of usage for the rune sticks, but they also challenge the old view of runes in another way as well, which leads us to the second point: how long the runes were in usage. Before the Bryggen find, it was believed the runes disappeared when the Viking Age transitioned into the Middle Ages, which the Bryggen find disproved. Runes were used long after it was believed they had been abandoned, and this finding has enlightened rune research to this day.

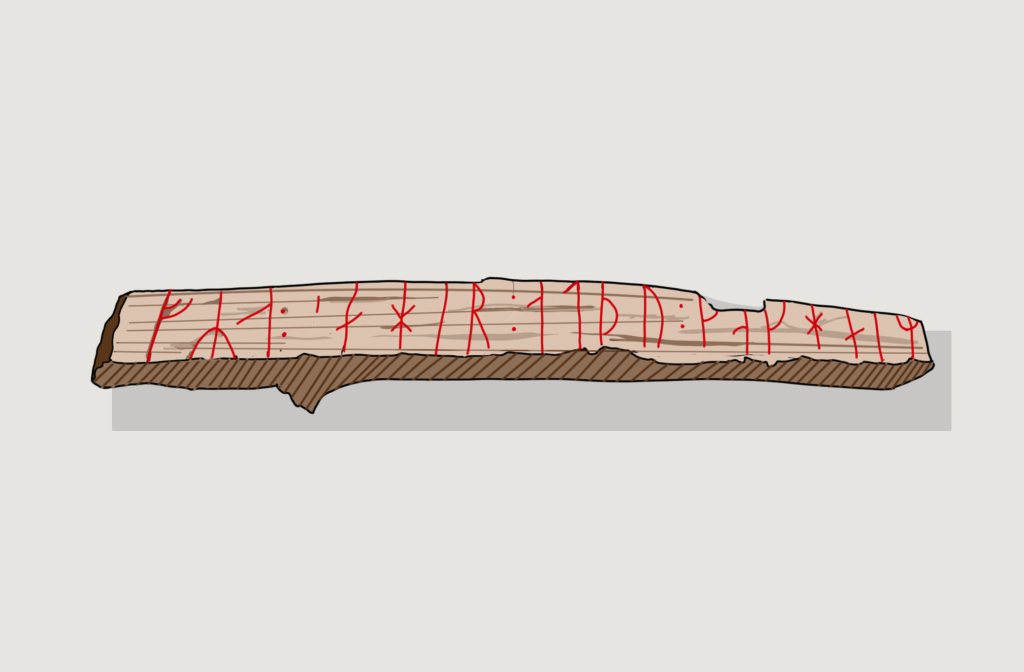

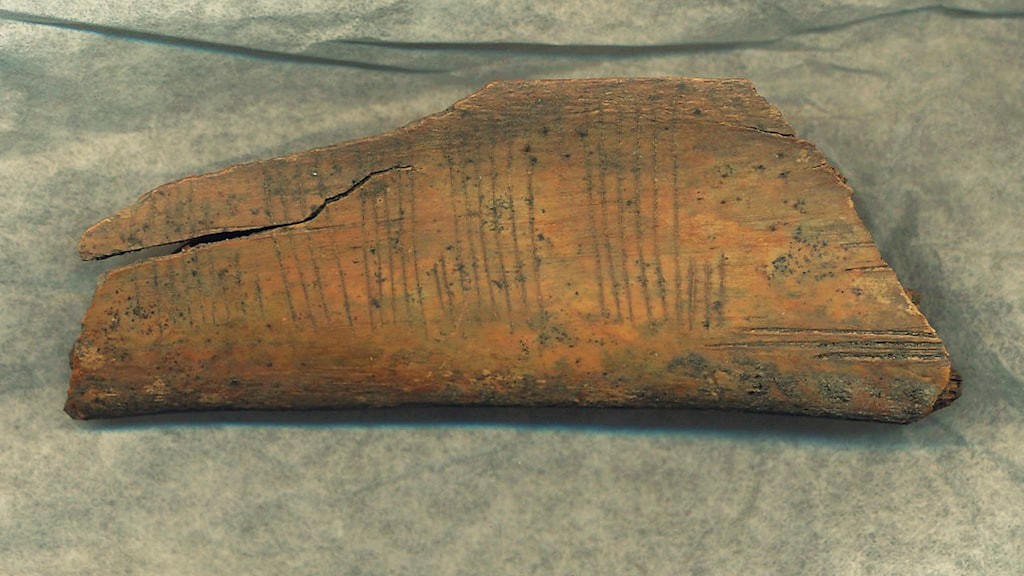

That said, did the Scandinavians use rune sticks before the medieval period? Yes, they did. One of the places where rune sticks have been found is in Sigtuna, near Stockholm, Sweden. However, the runes found here were not carved on wooden stick, but on bones—or at least, that is what archaeologists have found so far. As bone is made from harder material (with a high mineral content), these have survived the acids in the ground and have therefore preserved for archaeologists to find.

The city of Sigtuna was founded around year 1000 A.D.—roughly about the same time as the early Viking town of Birka was abandoned. The rune bones that have been found here have mainly been found in or around what once was long halls: buildings used for feasting or festivals. The bones contain similar messages as the ones in Bryggen, although they are not as many.

Our favorite rune bone was found in 1999, and was written in “ice runes”, a sort of encrypted runes. The translation took 15 years to crack due to this, finally completed by a runologist at the University of Oslo. The message read: kyss mik, meaning “kiss me”, in old Swedish. The reason that it sometimes can be quite hard to decipher runes, and in particular encrypted runes, is because it is believed that, even though people could write and read during the Viking age, it did not necessarily mean they were good at spelling—or even that there was a standard, agreed-upon spelling at the time—making rune translation quite a tricky business from time to time.

The loving message was, however secretive it might sound with hidden runes, not as secret, as ice runes were the most common hidden runes during this time period, and a good amount of the population was probably able to read them.

But we are glad to this day that people wrote not only high and mighty runes on stones, but left a piece of their everyday life, their hopes, work, love, desire, and heart behind. It is a comfort to know that people were just the same then as we are now. And we are glad these runes were deciphered and for us to know that sometime around 900 years also, one night at a feast in a firelit long hall, amongst cheering participants and good food, mead and song, a boy was in love with a girl (or vice versa), and sent a rune stick to ask for a kiss in the night.

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover photo: Anja Szyszkiewicz, Upplands Museum.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.