Pickled herring, schnapps, strawberries, and dancing around a maypole. What is this sorcery, and why would anyone in their right mind combine strawberries with pickled herring? Who are these crazy people? Well, we are talking about Swedes and Sweden’s most important tradition: midsummer celebrations (Midsommar). We do not only have IKEA to offer, believe it or not. If you visit Sweden sometime between the 20th and 26th of June, chances are you will end up at a party and stumble home in the wee hours. Who knows, you might even experience magic or meet a supernatural creature on your way. The date each year differs since Midsommardagen (midsummer day) is an official holiday (meaning people are free from work according to the calendar) since 1953 and always celebrated on a Saturday. Therefore, Midsommarafton (midsummer eve, which is the day people celebrate with great parties) takes place the Friday preceding Midsommardagen. What is Swedish Midsommar? Where does it come from, and how has it developed throughout history? Come with us on this journey and get to know more about this completely magical evening taking place each year in June.

Midsommar and Saint John the Baptist

Several theories surround the Swedish Midsommar celebrations. One of many states that Midsommar is a tradition that predates the process of Christianization in Scandinavia. For example, most people have heard of the so-called midsommarblot (midsummer sacrifices). While this is an interesting theory there are actually no reliable sources supporting it. Our pre-historic ancestors most likely celebrated the summer solstice, as many cultures have done and still do, throughout history, but the Swedish Midsommar tradition today cannot be connected to pagan practices. Midsommarblot is considered a rather new tradition and is commonly practiced within modern paganism in connection to Midsommar.

So, why do Swedes eat pickled herring and drink schnapps if not to honor our Norse gods? Well, the Nordic Midsommar celebrations have their roots in Christian traditions that are connected to Saint John the Baptist (Danish/Norwegian: Sankt Hans; Swedish: Johannes Döparen). The earliest Swedish source concerning Saint John the Baptist celebrations stems from 1555 where Olaus Magnus, a Swedish priest, and Catholic bishop, refers to Midsommar as the day where people gather and light up the night with bonfires (sankthansbål). Sankthansbål is an old tradition first recorded in Europe in the 4th century. Saint John the Baptist is still celebrated with bonfires in both Norway and Denmark, and the day is called Sankthans, compared to Sweden’s Midsommar.

The Maypole – Midsommarstången

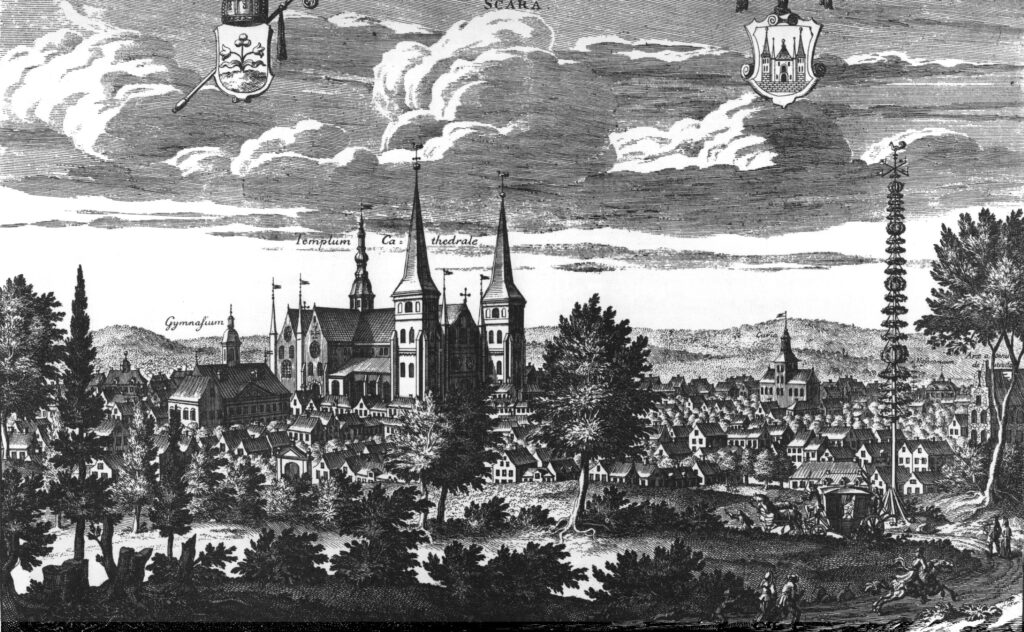

For some reason, Sweden did not fancy the bonfires and would soon let go of the tradition (even though bonfires are still lit on the 1st of May, but for a whole different reason). Instead, in the late Middle Ages, Sweden adopted the maypole from Germany and today this is the strongest symbol of Midsommar, being found in many private gardens throughout Sweden. The maypole (midsommarstången) is first seen in Erik Dahlberg’s Suecia antiqua et hodierna, drawn and published in the 17th and 18th centuries. This is a rather different version from what can be seen today. While it was a bit more complex early on, Swedes developed their own version in the shape of a cross, decorated with flower garlands at the ends. In modern times, the Swedish maypole has been discussed as being a phallic symbol, representing fertility. While fertility and the hope for good harvests are tightly connected to Midsommar and the solstice, the maypole should not be interpreted as a phallus. People are of course free to dance around whatever they like, but the Swedish maypole should be seen as an adaption of the Christian cross rather than a phallus.

The word “maypole” (Swedish: majstång) is somewhat misleading since it has very little to do with the month of May. Instead, it refers to the decoration (the Swedish word maja meaning decorating with leaves) in celebration of spring exploding with greenness. This is exactly what Midsommar is all about; celebrating Mother Nature and her ability to provide a good harvest and thus food on the table for the next year. This was the main reason society prepared for and celebrated Midsommar in 19th and 20th century Sweden. Midsommar was the highlight of the year and a day of joy, love, and coming together with friends, family, and neighbors whilst dancing around the maypole.

A combination of Christian beliefs and folklore

As has been explained, Midsommar is a Christian tradition. It is also very, very magical. As a matter of fact, Swedish Midsommar is a combination of Christian beliefs as well as supernatural elements from folklore (Swedish: folktro). For many years, the Swedish church fought hard to keep it a Christian tradition, but this was a pointless fight, and they finally gave up. This is where the magic happens! In sources from the 19th and 20th-century farmer’s society, several magical traditions are mentioned, some of which are still practiced today. An example of this is running barefoot or rolling naked in the morning dewy grass during Midsommar will apparently make you both strong and healthy for the rest of the year! Why not give it a go and see if it works? Gathering said morning dew was also a thing too. It was kept and used as a type of medicine, alongside the plucking of plants with healing properties as they were considered more potent during Midsommar than any other day of the year.

During Midsommar the veil between the worlds of the humans and the supernatural is believed to be almost non-existent. Hidden magical treasures are said to pop out from the ground, which makes it an excellent night for treasure hunters. It is also the perfect day to foresee the future. Girls picking seven different kinds of flowers and laying them under their pillow at night will dream of the man they will marry (we can promise you that many, if not most, Swedish girls have done this, including the author of this text). Picking flowers had to be done in complete silence, otherwise, the magic would be broken and the dream lost. Another tradition connected to the number seven and Midsommar night is jumping over seven fences, through doing this you could expect to receive both good health and successful harvests for the year ahead (and yes, we have done this in modern times too, sometimes gaining broken bones as a result)!

All in all, Midsommar is originally a Christian tradition. Later on, it developed into a hybrid of Christian traditions, for example, the cross-like maypole, and the adoption of folklore offering magical interpretations. In other words, we Swedes get a little bit of both, and it’s our most cherished day of summer (maybe even the year)! There is indeed something magical in gathering a group of people together to celebrate summer and the summer solstice, and it is a tradition well worth keeping and passing on to future generations. Some may wake up lonely with headaches and leftover dreams of our future spouses, but some may get lucky after impressive frog dances around the maypole after a schnapps too many!

Happy Midsommar to all of you! Maybe we will see you dancing around a maypole here in 2022? Be sure to send us the invite well ahead of time!

Oh, and by the way, if you want to see an example of a classic Swedish Midsommar, check this out!

About the author

Medieval Scandinavian Osteoarchaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts in Archaeology specialized in Osteology, from Uppsala university, Campus Gotland. My Bachelor's thesis focused upon the correlation between social status and health in the medieval church ruin S:t Hans in Visby, Gotland.

Master of Arts in Archaeology (two years), Uppsala university, Campus Gotland. In my Master's thesis I analyzed human remains (isotope-, bone density-, and morphological analysis) from individuals found at the Cistercian Roma monastery, Gotland. My aim was to get an understanding of the relationship between the living and the dead by studying both human remains and burial constructions in an isolated community context.

My future goal is to work full time as an archaeologist and also finish a PhD focusing at late Iron Age and early Medieval studies in Osteoarchaeology.