From its misty pagan origins, through its Christian rebranding, up to its metamorphosis into a time of merriment for all who wish to participate, Yule has meant many things to many people. Yule, today, is for many people just a synonym for Christmas, but this is to oversimplify it. Yule specifically has its roots in a midwinter festival observed by certain pre-Christian Germanic societies. Each had a slightly different name for the event: geol in Old English, jiuleis in Gothic, and jól in Old Norse. In Icelandic and Faroese it is still called jól, while in modern Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish it is now called jul—”Yule” is simply the anglicized spelling of the name.

As Christianity spread throughout Europe, Yule was one of the winter festivals that was absorbed and rebranded by the new religion. Some of its customs were ended, while others were retained but perhaps in an altered form. Of all the various Yule festivals, the Norse jól persisted in its pagan form the latest, as the Nordic nations were the last Germanic societies in Europe to be Christianized. The Christianization of jól was in some ways forceful, in others diplomatic, and it has continued to evolve organically ever since.

But the “elder” form of jól has received increased interest over the past century, not just from an academic standpoint but from a spiritual one. Followers of so-called “neopagan” religions like Wicca and Asatru have sought to revive the old, heathen jól in their own observances. However, this is a difficult endeavour, as the holiday lays bare one of the most yawning gaps in our knowledge of the pre-Christian Norse.

The fact is, we know terribly little about Norse paganism in actual practice. It is also unwise to generalize much, because it is very likely that it varied greatly through time and space. The whole Norse world might have acknowledged the same essential pantheon of gods, and probably marked the same major annual ceremonies. However, specific rituals may have differed among different regions of the Norse world, and different gods may not have been of uniform importance everywhere. And so even if a widespread pagan festival like jól had an “original” form, it is possible that it looked quite different when observed in different areas.

So what does this leave us to work with? References to jól in Old Norse literature are sparse, but a natural place to start. The first question we should ask ourselves is when?

When?

We can start with the Saga of Hákon the Good (king of Norway, 934-961 AD), from the Icelandic compendium Heimskringla, written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th c. AD. According to this saga, the pagan jól was a three-day event commencing at midwinter. This gives us a place to start looking, but with caution: the calendars used by the Old Norse were not the same as the one we are familiar with (nor, for that matter, was the Christian calendar of the day—more on that later).

We can piece together that the calendar used by the pre-Christian Norse was probably similar to other pre-Christian Germanic calendars, coordinating both the solar year (one solar orbit, roughly 365 days) and the shorter lunar year (twelve lunar cycles, 354 days). But the calendar used by Snorri, which had been used in Iceland since at least the 10th century, was different. While it still had twelve months, these lasted thirty days each regardless of lunar cycle, with extra days added mid-summer to fill in the day count of the solar cycle. The most basic division of the year was into two halves: “winter”, or the time of “short days”, from mid-October to mid-April; and “summer”, the time of “nightless days”, vice versa. By the reckoning of this calendar, midwinter—and therefore, according to Snorri, jól—would occur roughly in the middle of the Julian month of January.

Of course, as with most saga literature, the danger of relying too heavily on this account is that Heimskringla was composed around 1230 AD—nearly 300 years after Hákon’s death. There is always a certain doubt around the accuracy of Snorri Sturluson’s information about the pagan era, given the large time gap from when the events or traditions took place to when they were actually written down. Fortunately, in this case, we are helped by the testimony of a German missionary, Thietmar of Merseburg. He recorded that, in Denmark at least, jól did indeed take place in January. This account is earlier, dating to about 1000 AD—after Denmark’s “official” Christianization by Harald Bluetooth in the 960s, but much closer to the actual pagan era than the Icelandic sagas. In all likelihood, many Danes were still actively pagan at this point, despite being nominally Christian. Folk memory of the pagan festival was probably much livelier, and the rituals observed less altered by Christianity (even if king Harald had probably to an extent Christianized the event). The twist in Thietmar’s account was that, according to him, jól took place only once every nine years, but both accounts do agree on the time of year, at least.

This aside, various artefacts like runestaves point to a series of three days called “midvinternatterna” (Midwinter nights) occurring from roughly 12-14 January in the Christian calendar of the day, the Julian calendar. When converted into the Gregorian calendar, that used by most of the Western world today, this places the Midwinter nights from 19-21 January.

How, then, did jól become the late-December event we now know? At least in the case of Norway, we have an inkling of the story. The Saga of Hákon the Good, again, states that Hákon—a devout Christian, raised in England—had designs on converting the whole of Norway. But he understood, probably quite wisely, that to simply ban all pagan conventions outright was to invite rebellion from those who were only converting against their will—probably quite a large demographic. So, with jól, he began in a relatively gentle way, by simply changing the date of the event to coincide with Christmas, so that all Norwegians regardless of faith would celebrate their great winter festival on the same day.

This explains the change of date in Norway and, due to their close association, probably also the Faroe Islands and Iceland. Denmark’s adoption of the new date might have something to do with Harald Bluetooth, the first Christian king of Denmark (958-986 AD), who in 970 AD also became king of Norway. If the change of date had stuck in Norway, then Harald may have adopted the move in his own homeland for similar reasons. As for Sweden, this might have occurred under Olof Skötkonung, who became the first Christian king of Sweden in 995 AD—several decades after the Christianization of Norway and Denmark. Olof may have altered the date in imitation of his Christian contemporaries.

How?

So, now we have researched the timing of the event. Naturally, the next question becomes: how exactly did the event unfold, and how might that have changed when jól was eventually subsumed by Christianity? One answer to the second question is probably, “gradually”. Again, Hákon appears to have been savvy enough not to try and change the world overnight, and his adjustments to jól celebrations and religious life in general probably proceeded piecemeal as his position strengthened. Indeed, some later chroniclers referred to him unflatteringly as Hákon the Apostate, for this policy of pagan tolerance and assimilation of pagan practices, but it was likely a strategy that made him much more successful.

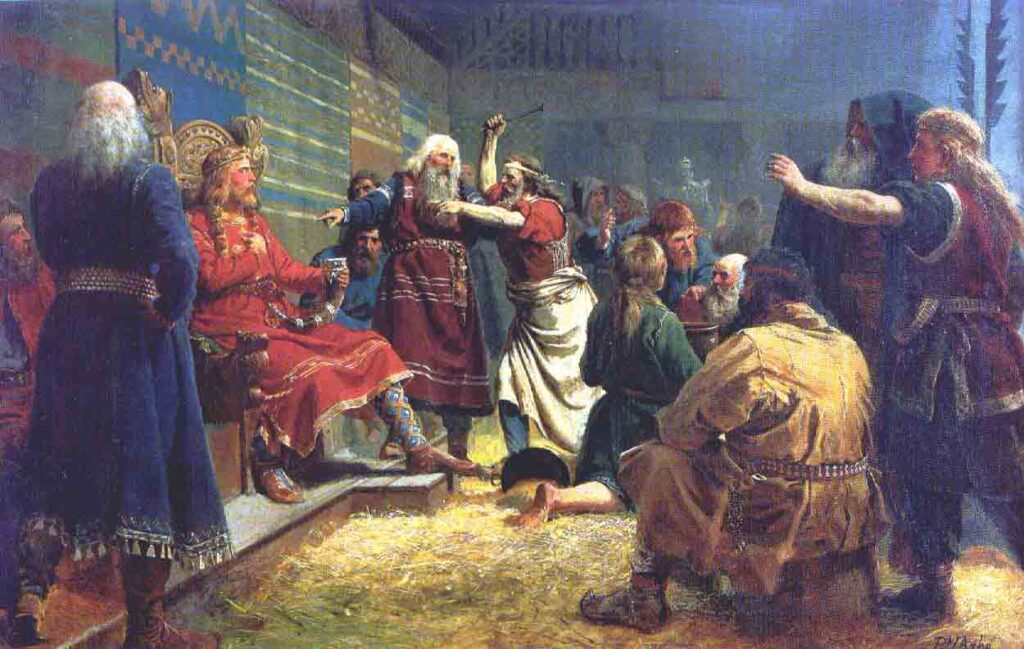

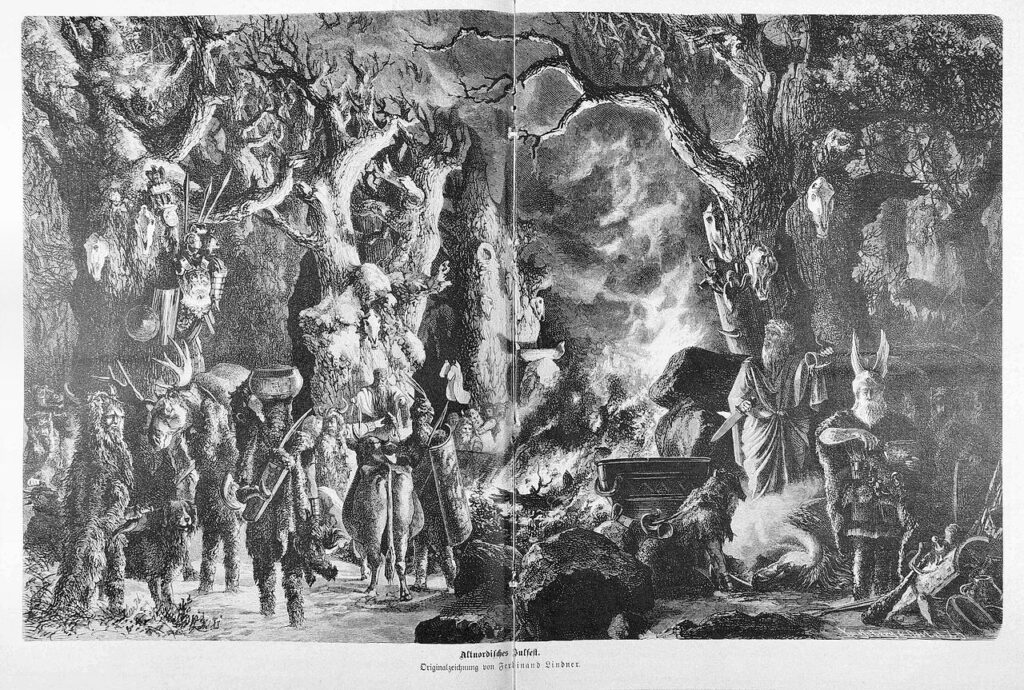

Let us begin with one fact that may make us a little squeamish in the modern world: jól was very likely a very bloody event. Hákon’s saga refers to the ritual sacrifice of a multitude of farm animals, whose blood was then spattered upon idols of the gods as well as on the attendees of the festival. This type of blood sacrifice to the gods was known as blót, and it was not limited to jól celebrations (multiple blót events are recorded throughout the Norse year), though the scale here may have been unusual. We do not know when this particular dimension of the festival was ended, but it is difficult to imagine it lasting long into the Christian era. At least, not in such a ritualized fashion. The livestock were not butchered only for the purpose of blood sacrifice, but also because their meat would then become the main event of the feast. This was an occasion in which not only “common” meats like mutton were served, but also more prestigious meats such as beef, horse, and pork along with the spoils of hunting and fishing. Of particular importance was the sonargöltr—a great boar who would be sacrificed to become the main course of the feast, but only after those in attendance had set their hands upon his fur and made their vows and oaths to the king (perhaps also devotions to the god Freyr, to whom the boar is sacred). This might be the reason that ham remains the meat of choice for the main course at Scandinavian Yule. As we all know, feasting has never ceased to be a Yule/Christmas tradition—and if you have ever attended a traditional Scandinavian julbord you know that astounding quantities of meat are still involved, with the general exception of horse (taboo in Christian law, though apparently not for IKEA). So, while Hákon and his like may have done away with the bloody anointments, there remained plenty of carnivory at Christian jól.

As an additional bit of confusion, saga sources make references to both jólablót (Yule sacrifice) and midvinterblót (Midwinter sacrifice). This has naturally caused a great deal of scholarly confusion, as the relationship between these events remains unknown. Some consider them to be different names for the same festival. Or, perhaps jól was the name of the festival as a whole and midvinterblót specifically referred to its sacrificial event. Alternatively, it is possible that they were entirely different occasions that unfolded simultaneously or in quick succession. There remains no consensus on this topic as of yet.

The biggest change, of course, was the religion and gods venerated by the celebration. Pagan jól was not a household celebration, but centred around a temple (hof) or outdoor altar (hög). Of the Norse pantheon, Odin of the Æsir (god of kings, who is himself referred to as Jólnir in some poetry), and Njord and Freyr of the Vanir (father and son, both associated with good weather and fertility) are singled out in Hákon’s saga as subjects of jól worship. This combination of gods seems to indicate that this was an occasion for the veneration of both kingly power and, common to winter festivals, prosperity of the land. Another source, the Saga of the Earls of Orkney, tells that midwinter in northernmost Sweden was a time of veneration to Thor of the Æsir—a god also associated with weather and agriculture, hence useful to appease going into the sowing season. Ancestor worship may also have taken place. Eventually, these aspects were replaced by a sole focus on Jesus Christ, whose date of birth had been set at 25 December by Pope Julius I (4th c. AD)—though this claim itself is ripe for contention, and may have been made to align with yet another pagan event, the Roman Saturnalia.

While pagan jól and newly-introduced Christmas were coexisting, Christian Scandinavians were naturally observing their holy day differently than their pagan counterparts. Most likely, Hákon the Good’s Christmas traditions were quite Anglo-Saxon in character, as he had been baptized and raised in England. Harald Bluetooth, whose conversion had been influenced by the Holy Roman Empire, most probably modelled his Christmas observances in a Frankish style. How much these differed is up for debate. But most likely, jól became in general a less lavish event, because far more important in the Christian calendar was Easter—the celebration of Christ’s resurrection. So, the full conversion to Christianity in Scandinavia might have been the point at which jól celebrations began to centre around households and families, rather than public forums (leaving aside the traditional Christmas mass). It is possible that the use of evergreen plants such as holly and mistletoe as Christmas decorations derives from the Anglo-Saxon influence, as these were common winter decorations in both pagan and Christian England. The Yule log was also probably borrowed in this way.

As to the tradition of Christmas presents, this may have many origins. Pre-Christian Scandinavia had always been a society that was heavily reliant on reciprocal, ritualized gift-giving as a way of strengthening friendships, alliances, and other bonds between people. This was not specifically associated with jól, though it is plausible that jól might have been a natural occasion to renew those bonds (the Saga of Hervör and Heidrek does describe the practice of swearing oaths on the boar to be sacrificed for the Yule feast). Others speculate that Christmas presents are derived from the Anglo-Saxon practice of giving alms to the poor in the weeks leading up to Christmas. But these explanations are not mutually exclusive, and they may have simply melded together as the years went by.

One tradition which certainly seems to have survived intact in the conversion of jól is the practice of drinking. Hrafnsmál, a poetic devotion written c. 900 AD to the pagan king Harald Finehair (king of Norway 872-930 AD), has it that he was so busy with his work of unifying Norway that he had to “drink jól outside”, rather than in the comfort of a hall. This can be taken to mean that drinking was such an integral part of this event, that to “drink jól” was a known expression. Hákon’s Christianization apparently saw no harm in this, for his own laws made it clear that ale was to flow in abundance for everyone during the days of jól, and celebrations should not stop until it was drunk dry. Like feasting, drinking at Yule is still going strong in Scandinavia, as snaps and other spirits are consumed, often alongside merry songs and witty ballads. A variety of drinks are staples of the julbord, many of them flavored with festive spices just for the occasion.

Summary

Overall, then, the evolution of Scandinavian Yule can be seen as the transformation of a lavish, public ceremony of both conspicuous sacrifice and consumption into a more publicly reserved, solemn religious occasion with more personal, intimate celebrations. It can also be seen as the transformation of a midwinter festival into something more closely aligned with the winter solstice (even if it had no ideological connection to the solstice itself). Later, it continued to evolve into a cultural phenomenon that transcends personal faith or cultural attachment: today, Yule is among the biggest calendar events in Scandinavia, and more broadly, Christmas is one of the biggest events in the world. It will be interesting to see how Yule continues to evolve going forward. But as long as it continues to bring light, joy, and meaning into the lives of those who celebrate it, its story is far from over.

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover image: “Julfest” by Knut Ekwall (19th c.).

About the author

Archaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada) and a Master of Arts from Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden). My specialisation lies in bioarchaeology broadly, with a primary focus on mammalian zooarchaeology, and a special interest in the Late Iron Age of Scandinavia (though you can occasionally catch me sniffing around Egypt as well).

In my Master research I conducted an osteological analysis of domestic dog remains from Valsgärde cemetery, Sweden. The aims were to identify the number of dogs buried at the site, reconstruct the appearance of the dogs, and identify any patterns and changes between the Vendel Period and Viking Age.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between humans and animals, domestic and wild, in societies throughout the world. Through archaeology, I hope to shed light on this crucial part of our shared heritage.