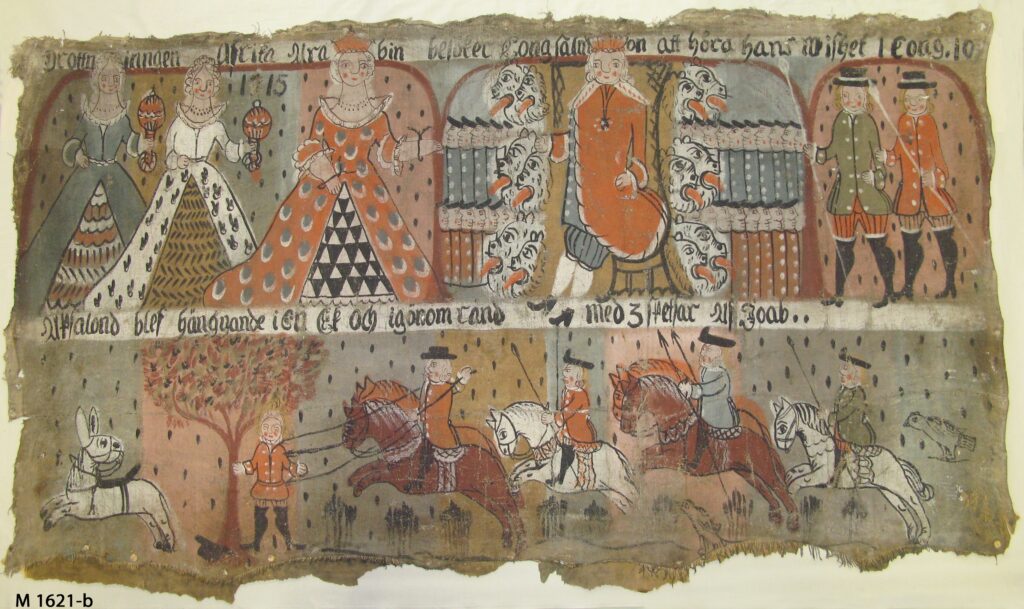

Decorative hanging tapestries (called “bonadsmåleri” in Swedish) were a particular type of Swedish folk-art popular between roughly 1750–1850 AD. The tapestries would be used to decorate walls of private accommodations or festive venues, often being hung up for a specific holiday before being rolled up for storage. The usage of these painted textiles started in the late medieval period in Sweden, with the oldest known tapestries dating back to approximately 1630 AD. The oldest example pictures the biblical motif of the three wise men bearing gifts to Christ. The tapestries were primarily in use prior to the industrialization of paper production, after which linen tapestries were replaced with more readily available and easy-to-reproduce paper versions. The old linen tapestries fell out of fashion in the late 19th century.

The depictions on these artworks vary from the everyday to the extraordinary. It is the religious motifs, depicting scenes from the Old and the New Testament, which encompass the latter type. Out of the tapestries that have survived to modern time, a majority depict events from the Bible. The popularity behind these motifs likely stems in part from the origin of the hanging tapestries as church-paintings. However, some tapestries also portray more profane and mundane tales of everyday life, including hunting, crafting, or other occupational activities.

What is perhaps the most interesting part of these tapestries is that they were not just commodities available for the aristocracy or the upper classes, but they were available to laypersons as well. A large number of the artists behind these beautiful tapestries were not trained painters, but rather farmers and craftsmen, who became skilled in painting by reproducing the same motif for years. They were so widespread in Swedish society that their periodic absences from the archaeological record can tell us that something terrible was afoot in those years—though art serves to stimulate the senses and spur cultural development, investment in art is typically far down the list of priorities during periods of starvation and poverty, when societies tend to focus their efforts on things with more practical function. So, years of famine in Sweden tend to coincide with years in which few to no new tapestries were produced. Conversely, when circumstances for Swedish farmers improved somewhat in the middle-18th century, this is marked by an increased the prominence of art-based objects, such as tapestries, in working class houses. .

The materials used to paint the linen textiles varied between artists and what they had readily available. The most common was a mixture of egg and flour and some variety of colorant, creating what is called tempera. The reason behind using this mixture was likely twofold: partially because it was of great importance that the paint had some elasticity and could be stretched (as it was painted on a soft and malleable canvas), but also because the materials for the paint needed to be readily accessible among the working-class painters. The art-style of the tapestries includes bright and warm colors, with friendly figures that are often depicted as smiling.

Today, these tapestries are considered a staple of the 18th and 19th century agricultural society of Sweden. The interest in this type of art was scarce for a long time, only rekindling after the Second World War. Prices for antique pieces have since then gone up, and so, thankfully, has the research into them. Hallands Museum in Varberg currently has the largest collection of tapestries, and Bonadsmuseet in Unnaryd, Halland, is a museum entirely devoted to the art of bonadsmåleri.

Photographs: Kerstin Petersson, retrieved from Digitalt Museum, https://digitaltmuseum.org/.

Text: Molly Wadstål. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Molly Wadstål

Archaeologist with a passion for archaeometry. I finished my bachelor’s degree in Norway at the University of Oslo, and also studied at Stockholm University to become an osteologist (bone specialist). I finished my master’s thesis in the Spring of 2021, in which I analyzed animal remains from the Viking town of Birka. I am currently working as a field archaeologist here in Norway.

My focus areas thus far have been on the later parts of the Iron Ages, specifically Birka and the Sandby hillfort. I am also very passionate about the Stone Age (in particular the Paleolithic and Mesolithic), and I am the happiest when I am simply working with archaeology, regardless of era. I am also very passionate about Archaeological science, particularly studies around bone.

As Junior editor and Illustrator, my work here at Scandinavian archaeology is to write articles, and to do more hands-on administrator work. A large part of the illustrations here on our website are made by yours truly.