Runes, the style of writing adopted in Scandinavia over a long period of time, have also been found in more widespread areas outside of Scandinavia. It is therefore not strange that the Futhark, which the runic alphabet is called, has undergone its fair share of changes and development in different directions during its period of use, thus resulting in several different types of futhark. All the different runes and local variations could be a bit confusing at first, but fear not! Here we will guide you through the jungle of the futhark’s rich history.

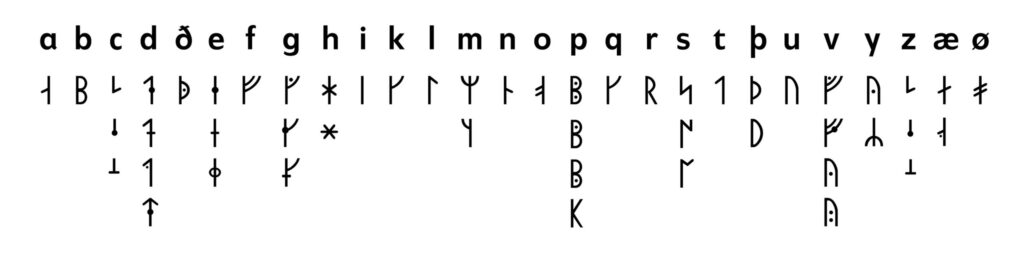

The word futhark, or fuþark, derives its name from the first six runes in the alphabet and the concept was coined in the latter half of the 19th century in runological circuits. The runes have, throughout their use, been altered by the dynamic changes of history which caused some runes changing both in appearing and sound, some disappeared completely and others remained constant throughout. In general, the futhark is divided into three parts with sub-categories: the Older Futhark, the Younger Futhark, and the Medieval Futhark. The main reason for the alteration in the futhark is that the spoken language and the sound picture changed. The runes are based upon how they sound, and when the language evolves, as well as the pronunciation, so do the runes.

Older Futhark

The Older Futhark (or Old Norse runes as it is called in Scandinavia), contain the first runes ever used and are based upon the Old Norse language. It was utilised used between the years 100 A.D. to about 700 A.D. In general, the Older Futhark can itself be divided into three categories: the Old Norse runes, the Intermediate Phase, and the Late Old Norse runes.

Based upon their appearance, the runes had a clear impact on the alphabet used in the Mediterranean and the Latin uppercase. However, the strong aversion to using those characters, displayed through several graphical innovations points to the native characters being used as a manifest for cultural individuality. The Older Futhark is mainly found on objects such as swords and jewellery and can only be found on a very limited number of runestones. Altogether, about 300 runic inscriptions contain the older futhark.

The Old Norse Runes

These runes were the first used and came to be during the Migration Period between 0-100 A.D. to 400. A.D. and contained 24 letters/sounds. The runes contain the oldest preserved language used in northern Europe and it is also therefore used as the foundation for all research within source text for the Germanic language stem. In its earliest phase, it had three characters that were smaller in size, but they later came to match the rest of the futhark. It also contained a handful of runes that were only used when the whole futhark was written, but never used in sentences or words.

The Intermediate Phase

The Intermediate Phase developed during the later Migration and early Vendel Period, 400 A.D. to 600 A.D. The graphical changes in the futhark during this period were few but included turning the smaller runes from the earlier phase into a larger size to match their counterparts. The number of runes in the alphabet were also reduced to 21.

Late Old Norse Runes

During the period of 600 A.D. to 700-800 A.D., the Old Futhark underwent a drastic development. The appearance and the graphic shape of the runes changed, as well as the number of characters, which were reduced down to 20 runes, slowly evolving into what would become the Younger Futhark.

The Anglo-Saxon Futhark

This is a side branch from the previously mentioned development. The Anglo-Saxon Futhark was developed from the Older Futhark and used in areas of Anglo-Saxon England from the 5th century onwards. The Anglo-Saxon Futhark incorporated 28 runes, instead of the previous 24 runes of the Older Futhark. It later became even larger, developing into a full 33-character futhark, a marked difference from the alterations made with its Scandinavian counterpart.

Younger Futhark and The Change

The Younger Futhark, or sometimes called the Viking Age Futhark contained 16 characters instead of the previous 24 and has several parallel futharks in use between 700 A.D. to 1100 A.D. This is the futhark which is preserved the most in stones and items. The reason for the reduction of runes is because of the drastic changes taking place around the 8th century regarding the language. The language, as well as its sound picture, changed. Words were shortened and changed vowels. The old pronunciation of the runes came out of use as a new way of speaking arose which needed new and developed runes that fitted for the new sounds. How this came into being in practice is currently up for debate with options being that the change occurred gradually, or if there was more of a sudden implementation of reform led by powerful individuals. The theories are based upon a very small collection of material from the transition period, and it is therefore very hard to establish which of the theories seems to be correct. The Older and Younger Futhark were used simultaneously, but after the years 750-800 A.D., the Younger Futhark became the standard. The Older Futhark was still used, but its area of use seems to have diminished and was now limited to special purposes, for example as hidden runes, as the knowledge of reading the runes slowly faded.

Because of the reduction of runes in the Younger Futhark, it is also the futhark with the most complex spelling system. Some of the runes represented several different sounds, but the spelling was always the same, provided that they originated from the same time period.

The Younger Futhark came in three versions based upon their structural differences: long twig, short twig, or rodless runes. These are more or less the same, but have a somewhat different appearance and were used for different purposes.

Long Twig Runes

The Long Twig runes, sometimes called normal runes, or Danish runes, are the most common. This is because they are the runes mainly depicted on runestones, which are the largest type of material culture to be preserved.

Short Twig Runes

Short Twig runes, or sometimes called Swedish-Norwegian runes, are a simpler and therefore faster and easier way of writing the long twig runes. With the reduction of the minor twigs, the short twig runes would be suitable to be used on wood for more everyday writing. The Short Twig runes were also occasionally featured on runestones, for instance they are commonly used on runestones in the Mälaren Valley and on the island of Öland, Sweden.

Rodless Runes or Hälsinge runes

This is the shorthand of the long twig runes. As the name suggests, this version of the futhark has no rods at all, only twigs. The only known runestones where rodless runes are depicted have been found in the Swedish county of Hälsingeland, thus leading them to be also named Hälsinge Runes. However, this is a name that should not been used as it can be misleading due to the Rodless Runes also being found in Norway carved on wooden sticks, as well as runestones containing mixed runes in other areas of Sweden.

Stugna Runes

Around year 1000 A.D. another sort of runes emerged that contained dots to cater for new sounds. Sometimes the dots took the place of the twigs, in other cases they were added to runes, making the Stugna Futhark become 19 runes instead of 16.

Medieval Futhark

During the beginning of the Middle Ages, the futhark developed even further, as a result of the Stugna Runes who were incorporated into the general alphabet and the futhark came to consist of 28 characters at its most. The Medieval Futhark combined both long and short twig runes alongside the Stugna Runes in order to match the spelling as much as possible. Another major change was that the runes no longer followed the order of the futhark and thus became an alphabet. This alphabet was used from the mid- 12th century and is said to be in use until after the end of the 13th century. However, runes were still used hundreds of years later in some parts of Sweden, both on grave stones, rune sticks, rune calendars, religious graffiti in churches and manuscripts.

Today runes are no longer used and it requires a lot of skill and knowledge in order to read them. It would certainly take a lifelong devotion to the subject in order to become skilled enough to read and understand the several different types of futhark.

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse, 2021. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

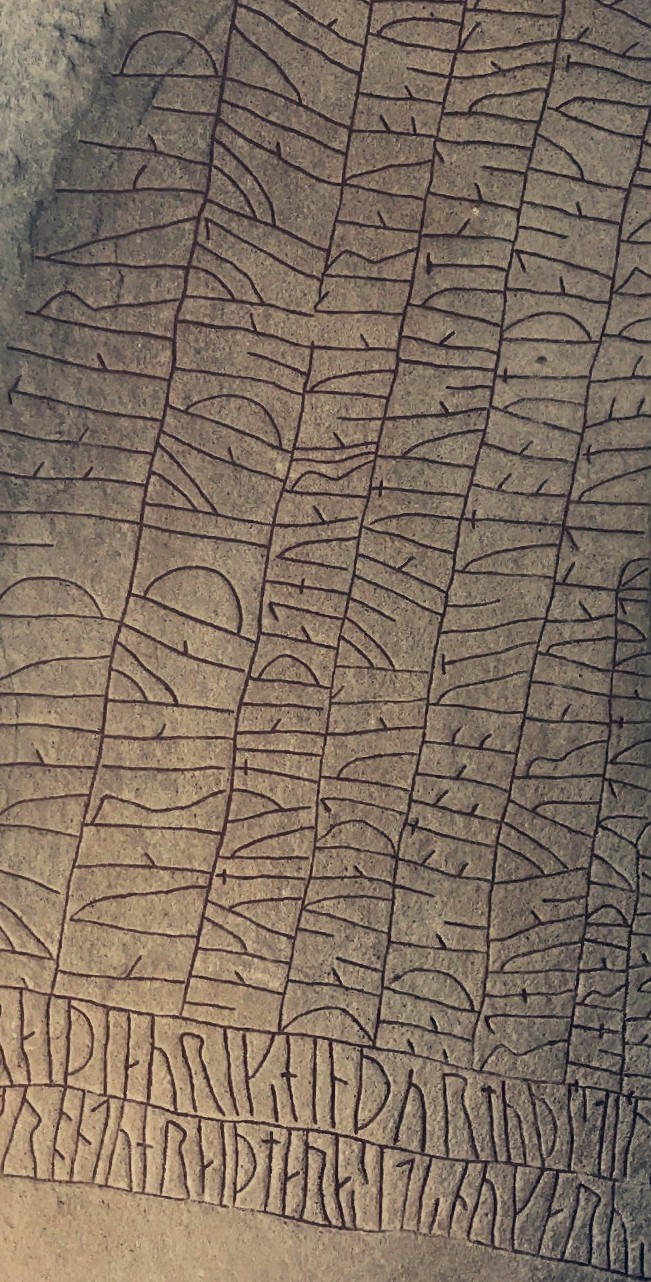

Cover Photo: Lovisa Sénby Posse, 2017. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Futhark graphics: Lovisa Senby Posse, 2021. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archeology.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.