Runes feature frequently in Old Norse literature, both in poetry and prose. In many cases, it seems like runes are used as a sort of metaphor for wisdom more broadly, and this makes sense: a person who has mastered the ability to read and write holds the key to boundless knowledge. But there are other occasions when the use of runes as literal magical symbols is clearly indicated, invoking charms, hexes, and prophecy. Generally, however, these are referenced only in passing, or only suggested vaguely, with scant detail given as to their use and application. Unfortunately, nothing like a “dictionary” of each rune’s magical properties exists, nor is there any comprehensive instruction manual for their use.

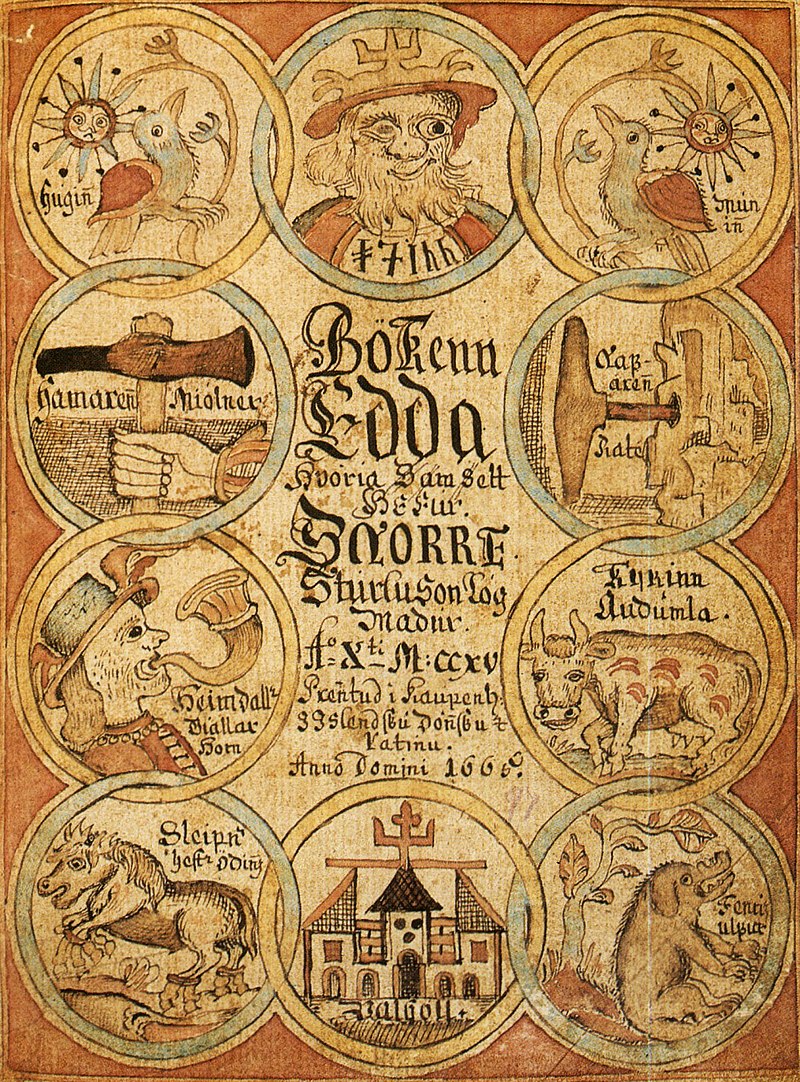

Nonetheless, we are not completely in the dark. Our best sources of information about this topic are two poems from that famous 13th century Icelandic manuscript, the Poetic Edda. This manuscript is a compendium of Norse oral traditions and poems from the Viking Age and earlier, and is one of our most vital insights into Norse mythology and folklore. The poems that interest us here are Hávamál (the High One’s Sayings) and Sigrdrifomál (the Lay of Sigrdrifa).

Hávamál

In Norse mythology, the master of the runes and all their magical associations is the the High One, the Allfather, chief god of the Æsir: Odin. Odin, as a god of wisdom and magic, was directly associated with the runes in a way that no other gods truly were. But this was not always the case. The Hávamál is a poem recited in the voice of Odin himself, largely a collection of his wisdom and sage advice, but in a section called the Runatál, Odin tells of his harrowing ordeal to acquire the runes from their keepers: the mysterious, dread Norns.

In of the more visceral images of Norse mythology, Odin tells of hanging by his neck from a branch of Yggdrasil—the cosmic ash tree that binds the universe together—a spear plunged into his torso, in a test of endurance and will. Beneath his feet ripples the Well of Fate, a great spring that feeds one of the main roots of the tree. There he waits for nine agonising nights for enlightenment to come to him. The wind blows upon him and his torture only intensifies each day, but he does not break, for he awaits what he knows to be a truly priceless reward. And then, finally, the Hanged God casts his eyes down into the murky waters, and beholds something rising from the depths. Greedily snatching at the water, he perceives his hand filled with mysterious symbols. With a shriek of victory and relief, he withdraws with his prize.

Thus did Odin acquire the runes. This story, as well as that of Odin’s sacrifice of an eye for a drink from the Well of Wisdom, is a striking example of the great lengths to which the god was willing to go to obtain knowledge and unravel the mysteries of his universe. It also illustrates the sort of value attached to runes in the Norse mind, that Odin was willing to undergo such an unspeakable trial to find them. And little wonder, for following his recollection of his ordeal, the god lists the many spells that he now knows, and they include the sort of abilities that many would pay dearly to have: charms for protection against physical, psychological, and magical harm; healing; escape from bondage; controlling others’ emotions; extinguishing fire; controlling weather; victory in battle and romance; and even necromancy. Of all these, only the latter is explicitly stated to be a runic spell, but given that this list follows directly from the Runatál, it is generally believed that these are all spells he acquired via use of the runes. Some researchers hypothesize that each spell corresponded to a specific rune in the Younger Futhark.

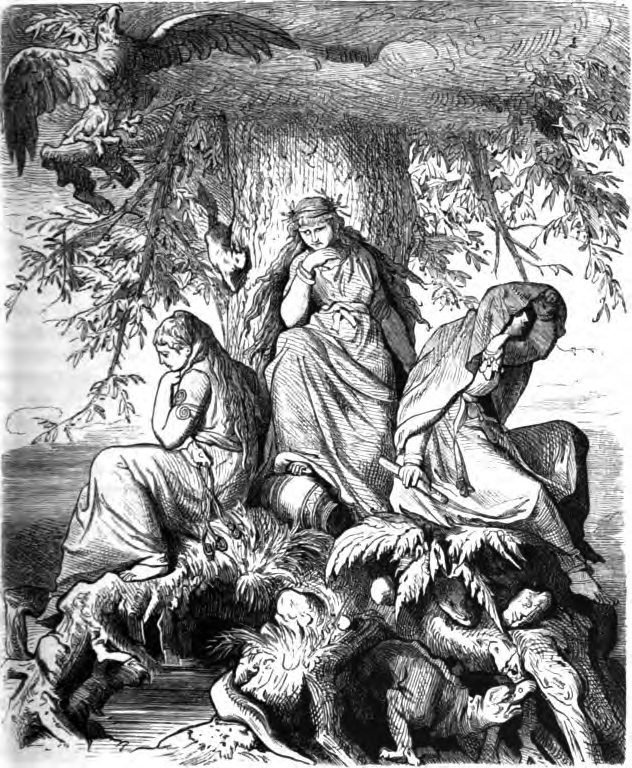

But where, then, did they come from? Before Odin’s arrival, we are told that three other beings made use of the runes. Their names are Urd, Skuld, and Verdandi, and they are the Norns—three mysterious women who tend the Well of Fate and the root that draws upon it. The Norns are something like the Fates of Greek mythology, subtly controlling the destiny of the world and all things within it. The Fates and the Norns famously both did so by a process of weaving, but in addition to this, the Norns projected their will into the universe by the carving of runes on wood. Another poem of the same manuscript, Völuspá (the Völva’s Prophecy), describes the Norns as carving on slips of wood, which is usually taken to mean incising rune sticks. It was when Odin espied these strange symbols that he travelled to commence his ordeal, deducing that even if he did not yet understand them, they must play a role in the wisdom of the three ladies. The exact nature of the Norns is much debated, but what is clear is that they are intimately tied up with the concept of fate, and as such with the dark art of prophecy (a branch of magic called seidr). Today, this is probably the most famous magical association of runes, and many neopagan movements carry out runecasting for fortune-telling.

Sigrdrifomál

We now turn to Sigurdrifomál, a very different poem that comprises part of the cycle of the great hero Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer. In this poem, Sigurd awakens a Valkyrie named Sigrdrifa from an enchanted sleep inflicted on her by Odin. When Sigurd asks her to teach him wisdom in return, the Valkyrie instructs him in the use of—what else?—rune magic.

Sigrdrifa talks of a wide variety of different types of runes. Victory runes, for…well, victory. Ale runes, to protect against bewitchment by drink. Birth runes, to assist in safely delivering babies. Wave/sea runes, to protect a ship in rough seas. Branch runes, for healing. Speech runes, to protect oneself from others’ hate and anger. Thought runes, to steel and sharpen one’s mind. Here, not only does she corroborate many of the abilities that Odin laid claim to, but also gives a greater insight into how runes were used to magical effect.

Often, it seems to involve carving the appropriate rune into the thing to be enchanted: a victory rune into the hilt of a sword, an ale rune into a drinking horn, a wave rune into a ship’s prow and rudder. Branch runes, used for healing, were not carved into the ailing person’s body (which would be rather counterproductive), but instead into the bark of a tree (possibly a beech, based on a later passage); interestingly, this also appears to be the method by which Odin reanimated the corpses of hanged people, carving the appropriate rune into the hanging tree. Birth runes were painted, not carved, on the hands and arms of those helping in the delivery. But speech and mind runes are somewhat less clear: Sigrdrifa talks of “weaving” speech runes into one’s speech, but how this should be done is ambiguous. There is still less about the application of mind runes. But certain of these spells involve not only marking or carving the appropriate rune but then invoking a deity with an incantation known as a galdr: with victory runes, one should invoke the name of Tyr, a god of war; with birth runes, the Norns or the even-more-shadowy Disir.

Aside from those listed above, Sigrdrifa explains that runes can be—and have been—carved into a multitude of different things. Fingernails, birds’ beaks, animals’ claws, horse’s hooves, and chariots’ wheels have all been marked with runes for reasons unknown (though sometimes guessable). Runes were even infused by Odin into that godliest of all drinks: mead. And it was by this route that the runes came to the other gods, the elves, and on to us, humble humanity.

Mystery and power

So, while we are left with far more questions than answers about the runes as magical artefacts, we can clearly see from their portrayal in the poetry of the age that they were a coveted and peerless source of power and knowledge. What we can attain from this is a little of the Old Norse attitude: that knowledge is power, and that it is the sort of power that is worth paying a very steep price for. Fortunately, we do not all need to suffer the same test as Odin in order to gain the runes for ourselves—we need only a curious mind and the will to learn. As the High One himself says:

“Wise shall he seem who well can question, and also answer well.”

– Hávamál, 35. Transl. Henry Adams Bellows

Cover Photo: Unknown. From the 18th century Icelandic manuscript ÍB 299 4to, page 58r, now in the care of the Icelandic National Library,

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Christopher Nichols

Archaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada) and a Master of Arts from Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden). My specialisation lies in bioarchaeology broadly, with a primary focus on mammalian zooarchaeology, and a special interest in the Late Iron Age of Scandinavia (though you can occasionally catch me sniffing around Egypt as well).

In my Master research I conducted an osteological analysis of domestic dog remains from Valsgärde cemetery, Sweden. The aims were to identify the number of dogs buried at the site, reconstruct the appearance of the dogs, and identify any patterns and changes between the Vendel Period and Viking Age.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between humans and animals, domestic and wild, in societies throughout the world. Through archaeology, I hope to shed light on this crucial part of our shared heritage.