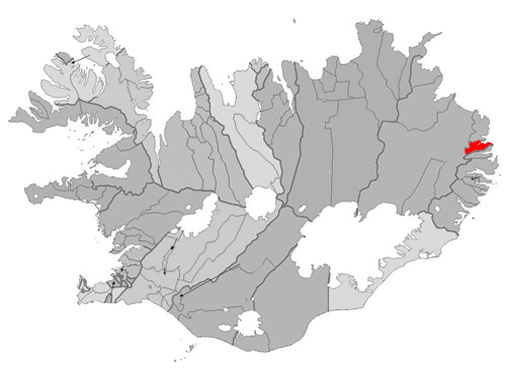

An archaeological excavation has been undertaken at Seyðisfjörður, eastern Iceland, where four burial mounds were discovered at the end of summer 2021. The recent discoveries are gaining recognition in Norway, owing to some ancient ties that have come to light. The excavation was a joint project between Antikva, Iceland, and NIKU, Norway. The primary focus of the excavation was an area northwest of the ancient farm Fjördur.

It was believed that Fjörður didn’t have any archaeological remains preserved in the area from before the 19th c. AD, when an avalanche sealed the medieval village—until now. It is known that there were several construction periods before, and after, the avalanche in the 19th century. No finds were expected from before the 17th c., however, so it came as a surprise to find evidence of human habitation right above the tephra layer from the eruption of the Veiðivötn volcano (dated to 1477 AD). As the expedition continued, they found human habitation layers in the area under a further tephra layer, from a previous volcanic eruption, Öræfajökull, in 1362 AD. Under this, medieval relics related to fishing and fish processing emerged.

During the preliminary survey, evidence of another landslide from the 15th c. was discovered along with one more that was thought to be prehistoric (as it was located much lower than the anthropic, or human-made, remains). However, later investigation showed that the prehistoric landslide turned out to be from after 1150 AD. The landslide sealed the area from the outside world, and thus preserved some remarkable finds.

The four graves are situated some 100 meters from the farm mound at Fjörður. The graves contained numerous artefacts dating earlier, to the Viking Age—including items such as beads indicating that the graves belonged to the upper class of society, not the typical Icelandic farmer from that period. In the four graves, well-preserved skeletal remains and extensive grave goods were found, alongside animal remains in two of the burials. No osteological analysis has yet been undertaken on the human remains, and a preliminary hypothesis of the sex of the individuals buried there is based on the nature of the grave goods. However, the skeletal remains will be examined by an osteologist this winter.

In one grave, a man was buried in a boat. The boat grave comprised a spear, a silver ring, a belt buckle in Borre style (fashionable from c. 850-950 AD), as well as numerous iron objects and other small items, such as beads. Pieces for hnefatafl, a popular Nordic board game, were also discovered in the grave. The boat grave is one of only 12 boat graves confirmed in Iceland, and the first of its kind in east Iceland (leaving aside a child’s grave containing a small boat). There is some evidence that one of the other graves may also have contained a boat, but this has not yet been determined (this grave was disturbed in the 1960s when an electrical pole pierced the mound). The tradition of boat burials for the elite was much more common in Norway and Sweden at the time.

Horse remains were present in two of the graves, one of which also contained the skeleton of a dog. This combination of animals is often found in high-status Viking Age graves in mainland Scandinavia.

The fourth mound appears to have been the grave of a woman. She was buried with a pair of oval bowl buckles, considered a classically “feminine” piece of attire, and a pearl necklace containing 11 glass beads. She also had a leather purse containing a Norwegian whetstone and some flint.

The whetstone has gained attention, as it is being believed that it likely originated from a quarry called Eidsborg, halfway between Stavanger and Oslo. The Eidsborg quarry was in use for centuries and the stones have some specific features, being distinctively lighter than in other parts of Norway. Eidsborg whetstones were of extremely high quality, and were a prestigious Norwegian export item during the Viking Age and the Middle Ages. However, further research is required to determine the origin of the stone.

These kinds of grave goods suggest the deceased were rich or of high social status, and all the objects have been sent to the National Museum of Iceland for further analysis.

Graves from pre-Christian times are fascinating in their variety of burial customs, and they are a valuable source of information for some of the earliest people to live in Iceland. As to who resides in them, we will never know for certain—but we are not entirely without leads here. In Landnámabók, the Icelandic Book of Settlements, a strong and knowledgeable settler by the name of Bjólfur, from Voss, Norway, is identified as the initial settler of Fjörðurá. As always, of course, it bears mentioning that Landnámabók was written some 300 years after the settlement of the island, meaning the accuracy of the records can be debated—however, the locations of farms as described in the book have indeed turned out to be fairly accurate. Not all these farms are named, and every chieftain brought a number of individuals with them of different social statuses, but archaeologically there is little doubt that the farm originates from the early settlement period in Iceland, and it cannot be ruled out that it is Bjólfur that is buried in one of the four mounds.

Text: Anna Sunneborn Guðnadóttir. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Image credits: Antikva EHF.

About the author

Anna Sunneborn Guðnadóttir

Archaeologist with a bachelor in archaeology from Uppsala University (Sweden), a Masters from University College London (UK), and a Masters from Uppsala University (Sweden).

During my masters studies I focused on the archaeometric side of archaeology - mainly Geographic Information Systems, geoarchaeology and optical microscopy. In my MA dissertation at UCL I used micromorphology and ceramic petrography to attempt to trace ancient artefacts to its manufacturing location based on modern soil samples and literary sources. My MA dissertation at Uppsala University was a digital analysis of a settlement based on the ceramics found during excavation.

I have a love for all things stratigraphy and geoarchaeological, and can often be found looking at stratigraphy wherever I can find it.

Very Interesting I have been to Iceland on our trip to Norway we have relatives from Voss and near there other Areas too ! Interesting Article , Thanks For Sharing !

Hi Gailen,

Thank you for your comment! We are glad you liked the article and that you found it interesting!