The Vikings’ use of ships as burial vessels is mentioned in several historical sources, and the Viking ship as a phenomenon was acknowledged already in the 1700s in Norway, long after anybody had actually seen any a real Viking ship with their own eyes. It wasn’t until the end of the 19th century that the 1000-year-old ships actually began to be unearthed, and then there was seemingly no end to it. Within 40 years, three Viking ships—the Tune ship in 1867, the Gokstad ship in 1880, and the Oseberg ship in 1903—had all been discovered in Norway alone. After the find at Oseberg, it took more than 100 years for another ship to be discovered in Norway. The use of georadar to find the Gjellestad ship in 2019 probably explains why, although ship burials are not a newly discovered phenomenon, they have in the last two years popped up in media more frequently than before.

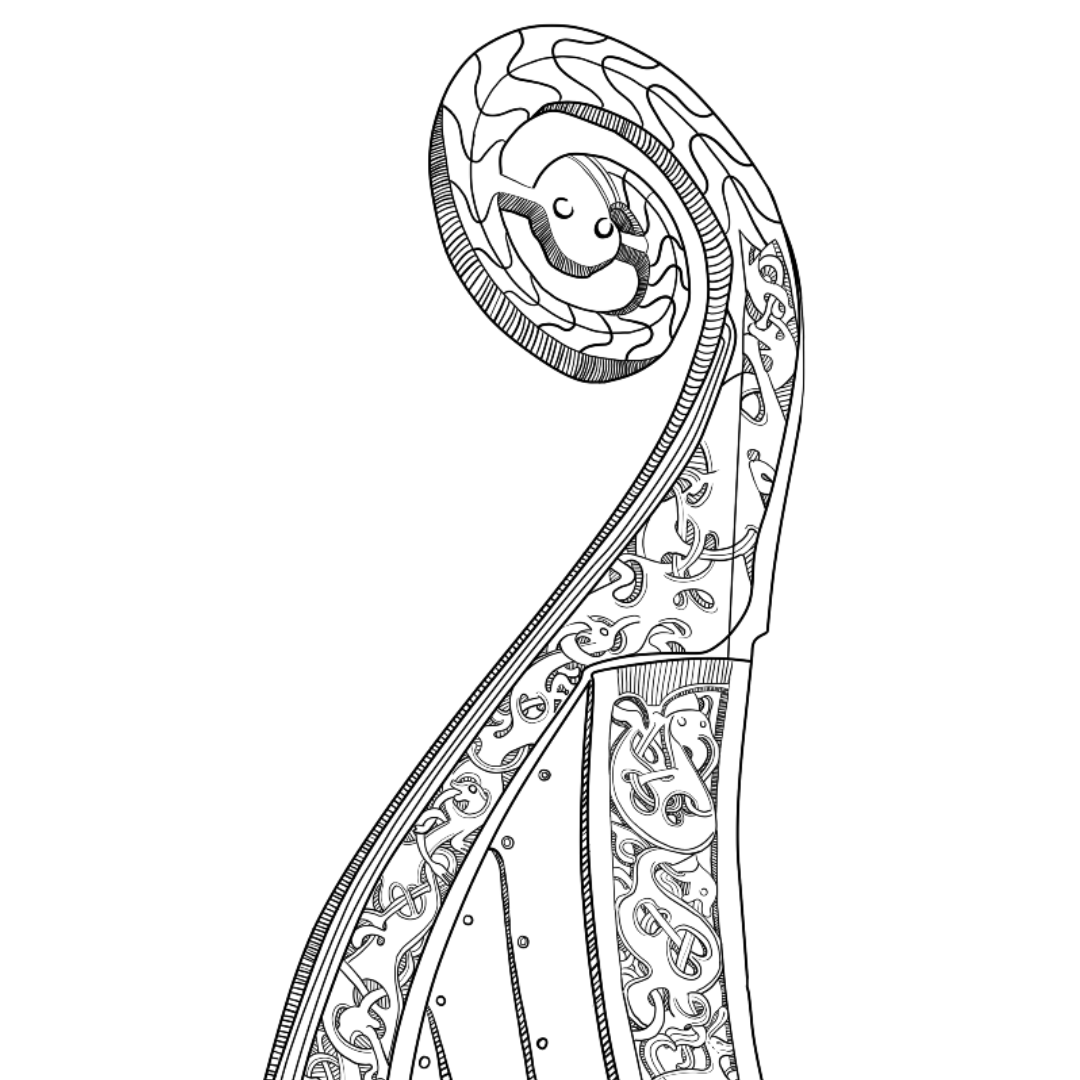

The Oseberg ship (dating to 800-830 AD), probably the best known of these examples, is a type of ship from the Viking Age known as a karve. It was an impressive 22 meters (71 feet) long, with space for 30 rowers. This remarkable ship was discovered inside of a grave mound in Norway in 1904, and has been displayed in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo since the early 20th century—until a week ago, when the museum shut its doors. But fear not, it will make its return in a newly built museum in 2025 or 2026.

Closing a museum for four to five years may seem drastic, but there is a good reason for it: the objects inside the museum are falling apart. Saving Oseberg is a project started in 2017, aimed toward attempting to rescue the wooden objects within the museum, which are in a terrible condition.

The Excavation

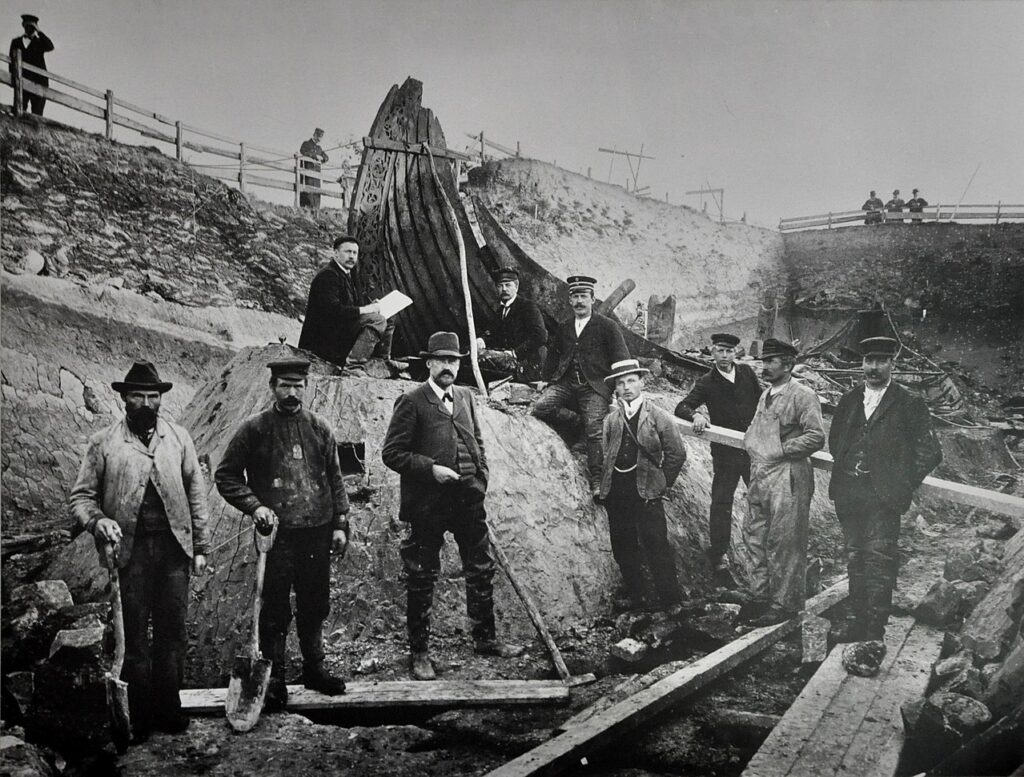

The excavation of the Oseberg ship is an historical event, beginning on a warm August day in 1903. Archaeologist Gabriel Gustafson was called to the Oseberg farm in Norway by Oscar Rom, who had uncovered parts of an old ship and wooden relics within a strange mound in his farmyard. Despite what must had been an irresistible temptation to begin excavations immediately, the decision was made to postpone it until the following season, as winter was coming.

The excavational effort began in early spring of 1904, and the work continued for two years. The reason behind the excellent preservation of the ship was in large part due to the sedimentary context: the surrounding mound soil was argillaceous, meaning that it consisted in large part of clay. This type of soil tends to preserve organic content exceptionally well since the tiny grains can form a hard “seal” around the object, preventing atmospheric oxygen from reaching it. The downside is that this likely made the ship exhausting to excavate, but because of it, approximately 90% of the ship had been preserved.

In the early 20th century, there were no clear laws or standards regarding who was in legal possession of archaeological findings on non-government-issued land. In this case, the ship was found in a mound on Oscar Rom’s private property. Once it became clear that it was not only a ship but one filled with impeccably-preserved objects, it became a legal issue between the archaeologists and the landowner. In the end, the farmer had to be bought out of his share of the objects with 11,500 NOK (adjusted for inflation, nearly 40,000 USD today).

Conservation and preservation of the ship

Figuring out a sustainable way of conserving the ship was a challenging task, especially because it had never been done before on such a large scale. Paul Johanssen was one of the important conservators, whose role it was to figure out just how to handle and preserve this much ancient wood. The solution was to soak the material in alum, a type of salt which appeared to stop the degradation quickly. This wasn’t a hastily-made decision: Gustafson had learned about alum treatment from a visit to the National Museum in Denmark in 1904, where it had been in use for almost 50 years. It therefore seemed like a safe approach.

While the alum-treatment seemed to work, it soon became obvious that it had not worked as a conservational method. The primary aim of conservation is to preserve an object in its original state, and to prevent it from decaying. However, what occurred instead is that much of the natural chemical content of the wood was replaced by the alum-salts, and the treated wood is now incredibly fragile.

As archaeologists, we primarily deal with excavating and uncovering finds, or conducting research and analytical studies on the material. This is also what is so often reported in news stories: archaeologists finding extraordinary treasures, or newly published ground-breaking research.

What is not shown is just how much effort and money is needed to maintain the materials once they are taken out of their burial context. As a result, many are not aware of just how difficult it can be to care for the objects that we excavate. Without the knowledge and the funding for proper conservational work, there is a risk that much of what we excavate ultimately decays. If we want to ensure that future generations get to appreciate archaeological treasures such as the Oseberg ship, we need to ensure that they do not decay. This requires professional conservators and materials, which of course cost money.

It was the aim of preserving Oseberg for a future generation that launched the project “Saving Oseberg”: to figure out just how to stop the degradation of the alum-treated woodwork and to help preserve the relics sustainably into the future. The museum finally received funding, and it is for this reason that the museum has now closed. A lot of work will take place behind closed doors, and in addition to being a massive help toward saving the Oseberg ship and the burial relics, it will also, hopefully, suggest new techniques toward the preservation of other wooden archaeological finds.

Text: Molly Wadstål. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover illustration: Molly Wadstål. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Molly Wadstål

Archaeologist with a passion for archaeometry. I finished my bachelor’s degree in Norway at the University of Oslo, and also studied at Stockholm University to become an osteologist (bone specialist). I finished my master’s thesis in the Spring of 2021, in which I analyzed animal remains from the Viking town of Birka. I am currently working as a field archaeologist here in Norway.

My focus areas thus far have been on the later parts of the Iron Ages, specifically Birka and the Sandby hillfort. I am also very passionate about the Stone Age (in particular the Paleolithic and Mesolithic), and I am the happiest when I am simply working with archaeology, regardless of era. I am also very passionate about Archaeological science, particularly studies around bone.

As Junior editor and Illustrator, my work here at Scandinavian archaeology is to write articles, and to do more hands-on administrator work. A large part of the illustrations here on our website are made by yours truly.

Molly, is there any way to donate to the restoration?

Hi Eric,

As far as I am aware, it is not possible to donate to the restoration of Oseberg, but I don’t think it is necessary. This project has actually been ongoing for a while, and recieved quite a hefty donation which will allow for a lot of conservational work to be done, as well as rebuilding the museum. We’ll just have to see what happens, and hope that they reopen soon! 🙂

/Molly